Regarding the period from 1852 to 1870, the following was discussed: Changes in the artist’s surname before taking the name Kunichika Toyohara, Seal other than ToshidamaStamp, Ohkubi-e, Ohkao-e, compositions such as medium shots, emotional expressions, manga with exaggerations and omissions, storytellers, etc.

Chapter 3 Discussion on initial activities

3-1 Independence and early activities as an ukiyo-e artist (until 1870)

Debuted in 1852 as “Yasohachi”

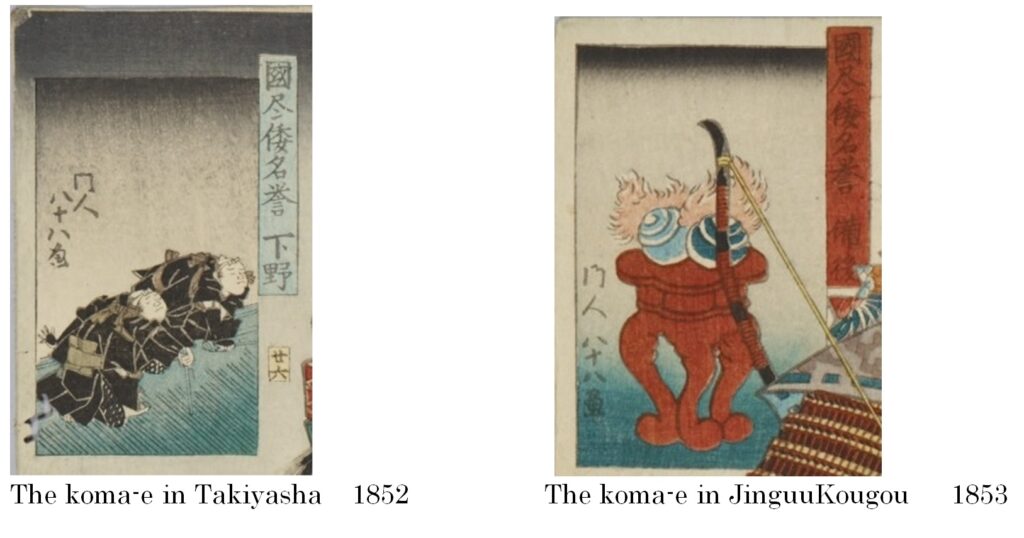

In 1852 and 1853, Toyokuni III released a set of paintings called Kunitsukushi Yamato Meiyo. Many of his students added background paintings to Toyokuni’s paintings, such as disciple Kunisada, disciple Sadahide, disciple Kunitsuna, etc. In the set of paintings, Kunichika added a painting of soldiers bowing down in the background to Toyokuni’s painting of “Masakado’s Daughter Takiyasha” in 1852, and signed it as disciple Yasohachi. Pictures added in this way are colled koma-e (pictures added within a small frame in the background). In the set of paintings, Kunichika added a painting of a jewel resting on a tripod in the background to Toyokuni’s painting of “Empress Jingu” in 1853, and signed it as disciple Yasohachi. The Theatre Museum has 65 paintings from this set, and while Kunichika added illustrations of soldiers bowing down and a jewel resting on a tripod, many of his students drew standing figures. It remains interesting to wonder why Kunichika did not paint portraits of standing figures that would have shown his skill. These are the only two paintings signed “disciples Yasohachi” and he used the name “Kunichika” from these works onwards. Regarding when Kunichika became a student of Toyokuni III, Sugawara Mayumi, in her Introduction to the Study of Toyokuni III (3), introduces the theory that he became a student of Toyokuni III in 1848 at the age of 14. Okamoto Hiromi (24, p348) writes that he became a student of Toyokuni III in 1848 at the age of 14. These paintings would have been painted in his fourth year after he became a student in 1848. On the other hand, Kojima Usui (1, p244) states that Kunichika became a student of Toyokuni III at the age of 17 (1851). Hiromi Okamoto (24, p. 347) states that Yasohachi “took on a job for the shuttlecock wholesaler Meirindo, and his actor paintings were well-received.” If that is the case, it seems appropriate that he painted this painting under the name “Disciple Yasohachi” the year after he became a disciple.

Full-scale debut 1854-1855

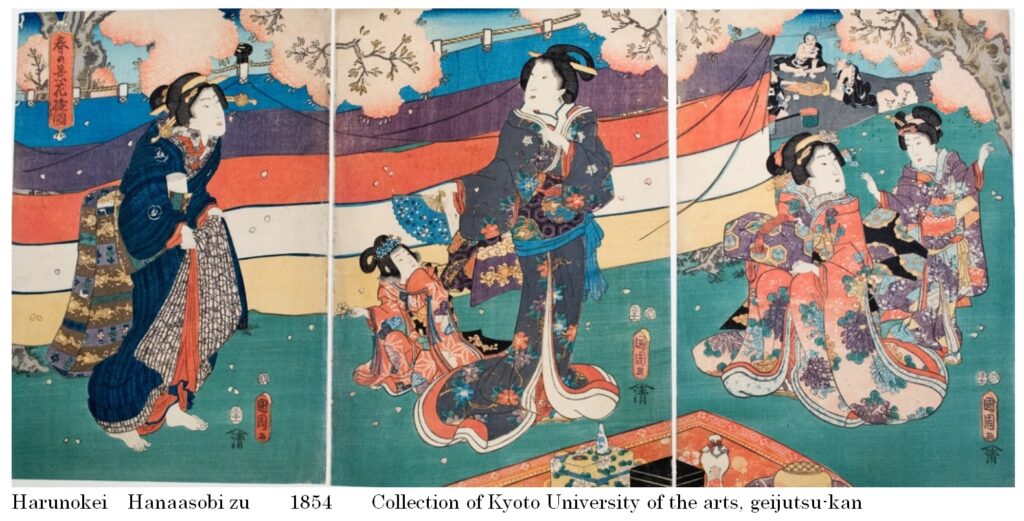

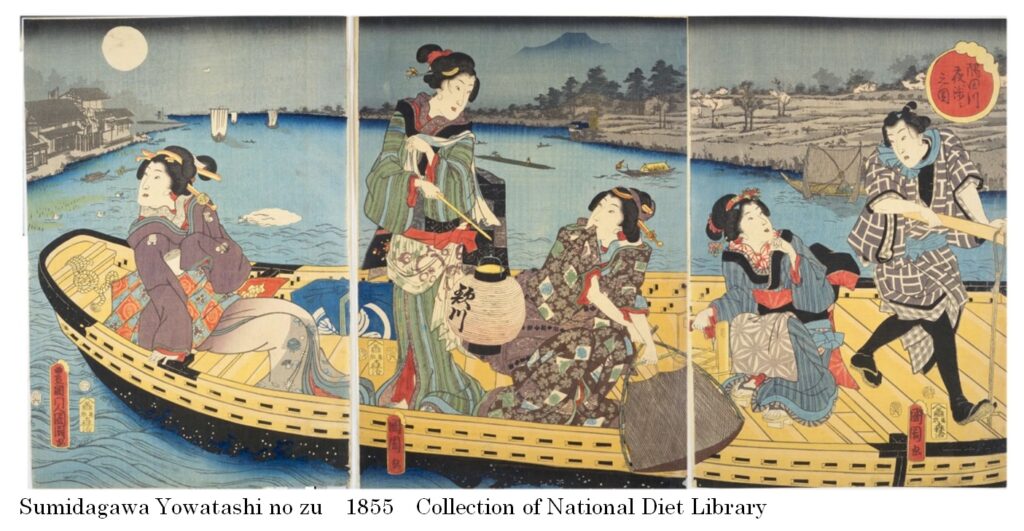

In 1854, he published “Harunokei Hanaasobi zu”. Kunichika’s signature is surrounded by a Tosidama Stamp and has a censorship stamp. This is a debut work as an ukiyo-e. This painting depicts the springtime enjoyment of Edo citizens, a place partitioned off by a curtain under a cherry tree where a drinking party (56) is about to begin. The woman in the center is thought to be the main character. She has no eyebrows and her teeth are blackened. She is likely the wife of a high-ranking samurai or a wealthy merchant. Her hair is in a Katsuyamamage. Her obi is tied in a single knot, and the strings on her obi indicate that she is concerned about getting her kimono dirty outdoors. The woman on the left has a round topknot and is probably a servant. She is holding up the hem of her kimono, worried about getting it dirty. The two are probably discussing the upcoming banquet. On the right, a girl wearing a furisode is holding a tiered box and talking to a small child. It depicts a cherry blossom viewing scene, but behind the curtain, a group of men who look like laborers are already drinking and having fun, saying things like, “What’s this? I thought it was a rolled omelette, but it’s yellow pickled radish?” Ukiyo-e search shows 2,409 ukiyo-e works that were created in 1854 and are currently on display, but most of them are kabuki plays, landscapes, elegant Genji stories, and courtesans, and there are few works depicting the daily life of the townspeople, such as Kunisada’s (Toyokuni III) “Tama River in Chofu” which depicts a woman crossing the river. Kunichika painted pictures in the niche genre of everyday life of the common people. In the corner of the background where the main women are drawn, behind the curtain, men are depicted drinking. This way of painting conveys the event of cherry blossom viewing to the viewer, rather than the viewer enjoying the cherry blossom viewing with the woman depicted. In the 1857 “Cormorant Night Party” (triplet), in addition to the main character Genji, another group is drawn in the left corner, expanding the story. This way of painting that expands the story is one of the characteristics. “Sumidagawa Yowatashi no zu” (1855) seems to have borrowed the composition from a painting by Toyokuni III. The characters in Toyokuni III are a picture of an elegant princess and a young lord having fun, but Kunichika’s subject matter for ukiyo-e is not the common people’s dreams as in the past, but rather common people in Edo, with a common woman and a spirited boatman. This is a so-called “yatsushi-e”, and it seems that this was the starting point of Kunichika’s style of painting, which aimed to create ukiyo-e with commoners as the protagonists. Kunichika’s painting depicts a scene of people crossing a river on a quiet moonlit night while chatting, with supple body movements that give the impression of movement, and even their voices talking and laughter are vividly depicted. The moon is reflected on the surface of the river in the middle ground, swaying in the waves. Fields spread out on the right bank, and sailing ships and mountains are painted in the distance, with the river stretching out as if it were connecting to the distant sea. At this point, Kunichika already had a clear direction for the subject he was trying to paint, that is, he was trying to paint something elegant and common, a yatsushi-e painting. No matter who the model for this painting was, it is a wonderful work that evokes a variety of thoughts in the viewer who looks at it objectively.

In 1855, Kunichika drew simple illustrations under the name “Ichiousai” for “Oomisoka Akebono Zoushi,” written by Santou Kyouzan and illustrated by Yoshitsuna. This was Kunichika’s debut in the field of illustrations. He did not illustrate a book by his master Toyokuni III, who had illustrated many of the kusazousi.

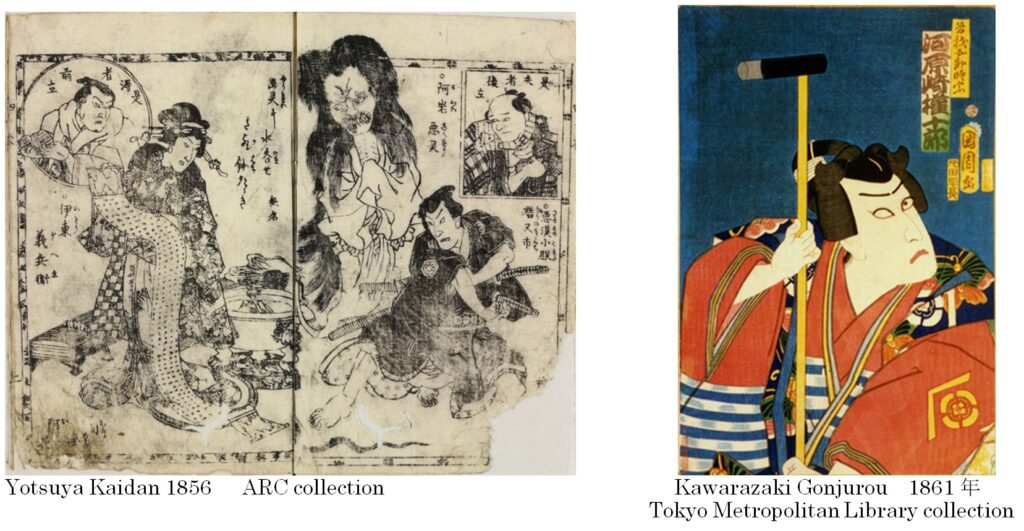

Around 1856-1858

After his painting’s debut, many works in the field of illustration can be found. From 1856 to 1858 he drew illustrations on kusazoushi, and the names “Ichiousai”, “Ichiousai Kunichika” and “Kunichika” were used. Names such as “知哥 chika” and “くにち kunichi” were also used for some illustrations. His debut work as an illustration artist was “Yoshinaka Yuusenroku” in 1856, under the name “Utagawa Kunichika.” The works for which he drew illustrations in illustrated books were “Yoshinaka Yuusenroku,” “Yotsuya Kaidan,” and “Wakan Musha Kagami” in 1856, “Iga no Adauchi,” “Yoritomo Yoshitsune Ichidai-ki,” “Yorimitsu Oeyamairi,” and “Shiraishi Monogatari” in 1857, and in 1858 there was a slight decrease in the number of works, such as “Kachikachiyama” and “Iga Goe Adauchi,” and it was a period when he also drew simple illustrations for other books. These three years were a time when he painted and illustrated various genres. In kusazoushi, he drew a picture in which warriors are active. Kusazoushi is more of a storytelling illustration than an ukiyo-e, so the expression of intense movement was skillfully drawn. The paintings also depict ordinary people, with a variety of facial expressions. The illustrations are full of expressive faces, and say things like, “Okay, let’s do our bit,” “Thank you very much,” “Oh come on,” and “Damn it.” It’s as if the illustrations are talking.

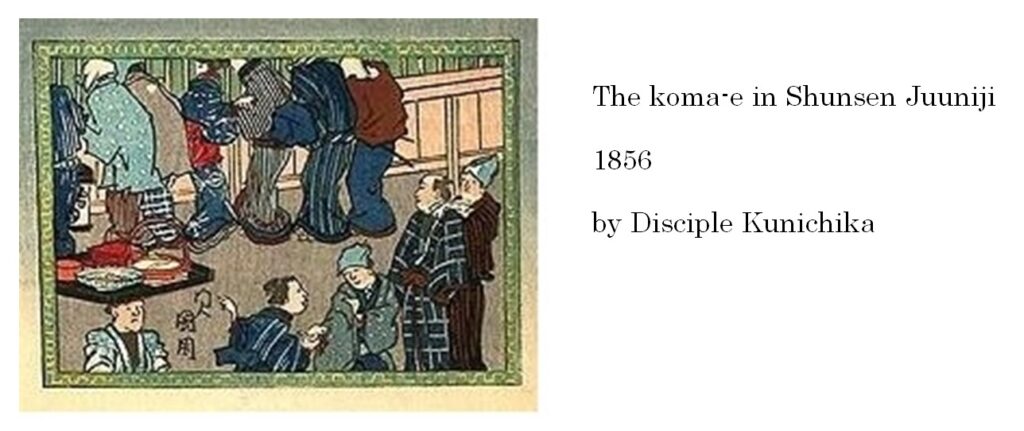

In 1856, he created a frame for Toyokuni’s painting “Shunsen 12ji” (see Chapter 2, 1856), signed “disciple Kunichika.” He painted a townsfolk peering through the lattice at Harimise (56), signing it desiple Kunichika. Toyokuni III painted a courtesan reading a long letter she had received. In the street, townsfolk peer through the lattice, some of them wearing headscarves. The woman also seems to be peering. In the street, a woman is talking to a timid man. A man from a soba restaurant passes by carrying a delivery tray on his head. Through his frame, Kunichika conveys the situation of a courtesan quietly reading a letter in the inner room, while many people are passing by in the street, peering into the red-light district. Compared to the 1852 panel, the 1856 panel packs in a lot of information and is more vividly depicted in a limited space.

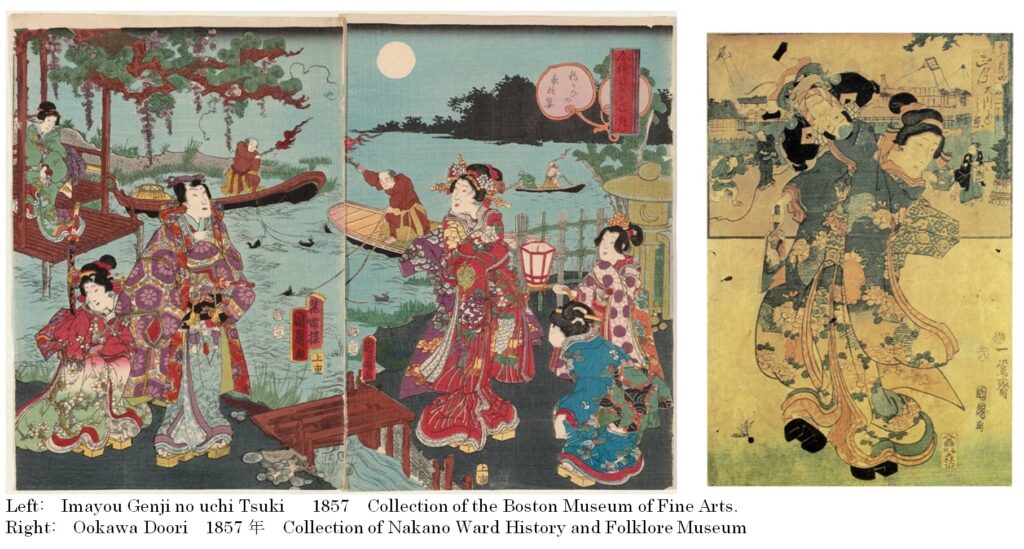

In “Imayo Genji no Uchi Tsuki” painted in 1857, the pattern of the kimono is carefully drawn, giving it a flashy impression, which is also a characteristic of Kunichika. Publisher Ueju completed this painting in two panels. Publisher Santetsu added one more panel and released it. It was thought that the theme would be blurred if it was made into a Triptich. It remains to be seen whether the decision to add to the two-panel set was Kunichika’s or the publisher’s. “Okawa Doori” painted in 1857 depicts a peaceful New Year’s atmosphere. On New Year’s Day, a young girl with her hair tied up in a high bunting (56) misses the feather of her shuttlecock while trying to avoid a falling kite. There is movement in the way her right foot is lifted up as she loses balance. The way she twists her body is skillful. In the background, a boy who let the kite go is chasing it, and the story is well depicted. Behind the woman are samurai, townspeople, and children celebrating New Year.

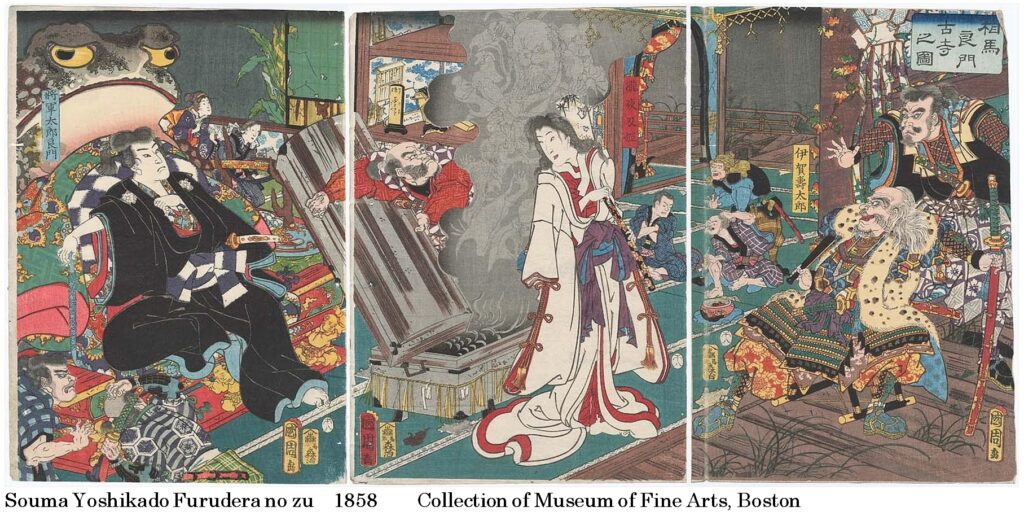

In 1858, he suddenly started to paint ukiyo-e in a variety of genres. His works include “Nijigatake Somaemon” which depicts sumo wrestlers, “Tosei Bijin soroi” which features common people as the main characters, “Sericulture”, “Asakusayama Kinryuzan Ichi no zu” which depicts the city, “Akushichibei Kagekiyo and Kumagai Kojiro Naoie” a large-headed painting, “Genji Gosekku no Uchi July Tanabata Festival” a Genji painting, the wonderful manga painting “Souma Yoshikado Furudera no zu” and the controversial “Meichi Hikyoku Heike Ichirui Kenzu.” Among these, the composition of “Nijigatake Somaemon” is very similar to “Kurume Onogawa Saisuke,” which was painted by Toyokuni III the previous year, but as with “Sumidagawa Yowatashi no zu,” which was painted in 1855, it is likely that he used his master’s painting as a reference. The illustrations in “Soma Yoshikado Furudera no zu” also tell a story. As Shogun Taro Yoshikado and his subordinate generals look on, the sorceress Princess Takiyasha brings in a large box, and when she opens it, a monster comes out in a puff of smoke. We can see the surprised expressions of his subordinates, the way Yoshikado glares, the soldiers making some kind of commotion in the back room, and behind Yoshikado, the giant toad that gave Yoshikado his sorcery staring into the room. In the background on the left, there are two women, also doing something unrelated and talking, and it’s fun to imagine what each one is saying. The illustrations are a cute comic, a picture story made up of fun pictures drawn without any sense of reality.

Around 1859-1863

Between 1859 and 1861, the number of ukiyo-e prints he painted and kept increased year by year. In 1859 there were two, in 1860 nine, in 1861 ten, in 1862 92, and by 1863 the number had risen to 279, marking a period when Kunichika’s reputation and popularity as an artist was on the rise. The ukiyo-e he painted included Genji stories, courtesans, customs and culture, Landscape paintings, war stories, and actor pictures. During this period, Kunichika painted a wide range of pictures in many genres.

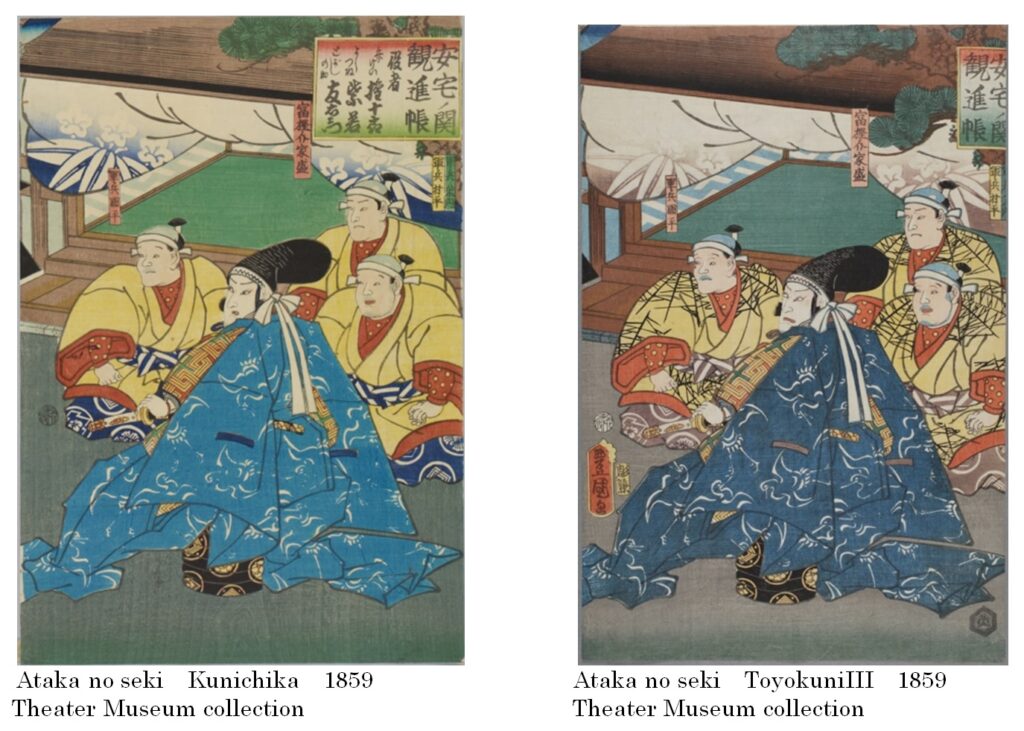

Among them is an interesting work from 1859, “Ataka no Seki Kanjincho.” Kunichika used Toyokuni III’s woodblock to create a work that appears to have been re-carved with only the face of Togashi no Suke Iemori, and published it with the actor’s name in addition to the cast name. This painting suggests the possibility of the reuse of woodblocks and the fact that, as a regulation of the Tenpo Reforms, it was forbidden to include the actor’s name and the cast name on a single painting, but in violation of the regulation, both were included.

When Kunichika painted women, he carefully drew the patterns of their kimonos and painted them with elegance. His distinctive style can be seen in works such as “Hanamori Bijin Soroi” (1859), “Hachikanjihisakonotekomae” and “Shigeoka” (1860), “Oiran

Takigawa and Others” (1861), “Shunshoku Shuchu Hanaasobi” (1862), “Sonoyukari Kuruwa no Akebono” (1863), and “Genji no waka Ohmihakkei” (1863). The picture becomes more colorful, but this flashiness gives it a commoner impression, and Higuchi Futaba(47) remarks that full-body portraits of beautiful women and illustrations for woodblock prints do not look sophisticated. Kojima Usui(1, p241) introduces “Tsuyasugata keshoujiman (This picture is not shown in this article)” from 1866 and states that even the masterpieces and fine works are without exception half-body paintings (medium shots), semi-large head paintings, and large head paintings (close-ups). He also highly praises “Hauta Toranomaki” from 1862 for the daily life of courtesans, but states that “Hanamori Bijin soroi” from 1859 (the 6th year of the Ansei era) is very poor. Regarding Kojima Usui’s evaluation, I cannot agree with him completely because his criterion seems to be “how it compares to traditional ukiyo-e”. For example, the paintings in “Hauta Toranomaki” are paintings of daily life, not paintings that admire beautiful women. It is hard to imagine that Kunichika was trying to paint portraits of beautiful women in the first place. Bijinga are paintings that admire the appearance and posture of the women, but Kunichika painted them as the daily actions and stories of women, that is, “Yatsushi-e”. Therefore, although his medium-shot portraits of beautiful women are highly regarded, they are not Bijinga. Although the medium shot paintings are highly praised, they are not beauty paintings after all. Regarding bijin-ga (portraits of beautiful women), Tanabe Masako(23, p6) states that Hishikawa Moronobu painted popular courtesans and geisha as ideal beauties, and then Suzuki Harunobu painted popular women such as Osen and Ofuji, and Utamaro painted Okita and Takashima Ohisa, but the faces and figures of these women were not painted with individuality, but as ideal beauties. Kunichika painted yatsushi-e and stories. To evaluate his paintings as bijin-ga is to compare paintings with completely different concepts to the genre of ideal beauties established by Harunobu and Utamaro, and this is a fundamental mistake. Inoue Kazuo(72) states that Kunichika’s “Bijin-ga” well depicts the customs of the time and does not miss the hectic flow of time. I may be overly concerned with the word “Bijin-ga,” but I think that the term “women’s customs paintings” describes Kunichika’s paintings.

In 1862, the number of stored prints found through the Ukiyo-e Search increased to 86 (the number is slightly lower in the Ukiyo-e Search as works from 1862 due to an obvious misreading of Eto), and many actor prints were drawn. It is thought that the increase in the number of prints is also related to the fact that from 1861, the names of the actors and the names of the characters in the play were written simultaneously. During this period, Toyokuni III also released a huge number of actor prints. In 1863, the number of stored prints found through the Ukiyo-e Search increased to 279 works. Furthermore, 1863 was a turning point for Kunichika.

1) He had a disciple: His disciple Otojiro drew illustrations for the kusazoshi “Karimakura Tatsumi Hakkei” drawn by Utagawa Kunichika. This indicates that he already had a disciple, and that the disciple was capable enough to participate in the work. Otojiro’s real name was Morikawa Otojiro, and he was a disciple of Kunichika. His artistic name was Morikawa Chikashige, and he was active in the early Meiji period.

2) Works on request: “Takukai Shuen no zu” was the first work found to be on request that is thought to have been sponsored. “Moko dekisen no zu” from the same year was also a work on request. It is believed that his popularity and reputation grew.

3) Painted landscapes: These paintings are part of the Gojouraku Tokaido series, a series of numerous paintings by artists of the Utagawa school, such as Toyokuni and Kunichika, that were produced in honor of Shogun Tokugawa Iemochi’s visit to Kyoto, alluding to post towns and the procession of Shogun Iemochi. This matter will be discussed further in “Chapter 3, 3-4, Landscape Paintings.”

Around 1864-1870

In late 1864, Toyokuni III, his master, passed away, and Kunichika painted a memorial painting. As Kuniyoshi had already passed away, Kunichika became a popular artist in the field of actor paintings. According to a search on Ukiyo-e, Kunichika’s paintings currently in storage were 410 works in 1864, 633 works in 1865, 542 works in 1866, and 1,072 works in 1867. The number of works in 1867 was the highest in Kunichika’s life. He began to paint mainly kabuki plays and actor paintings. Many of his actor paintings were medium shots of kabuki actors from the waist up. In this composition, he carefully painted the intense movements of the play, the climax, and the emotional expressions of the actors’ performances, which convey their emotions with small movements. Standing figures that explain kabuki plays, so-called long shot paintings, have decreased.

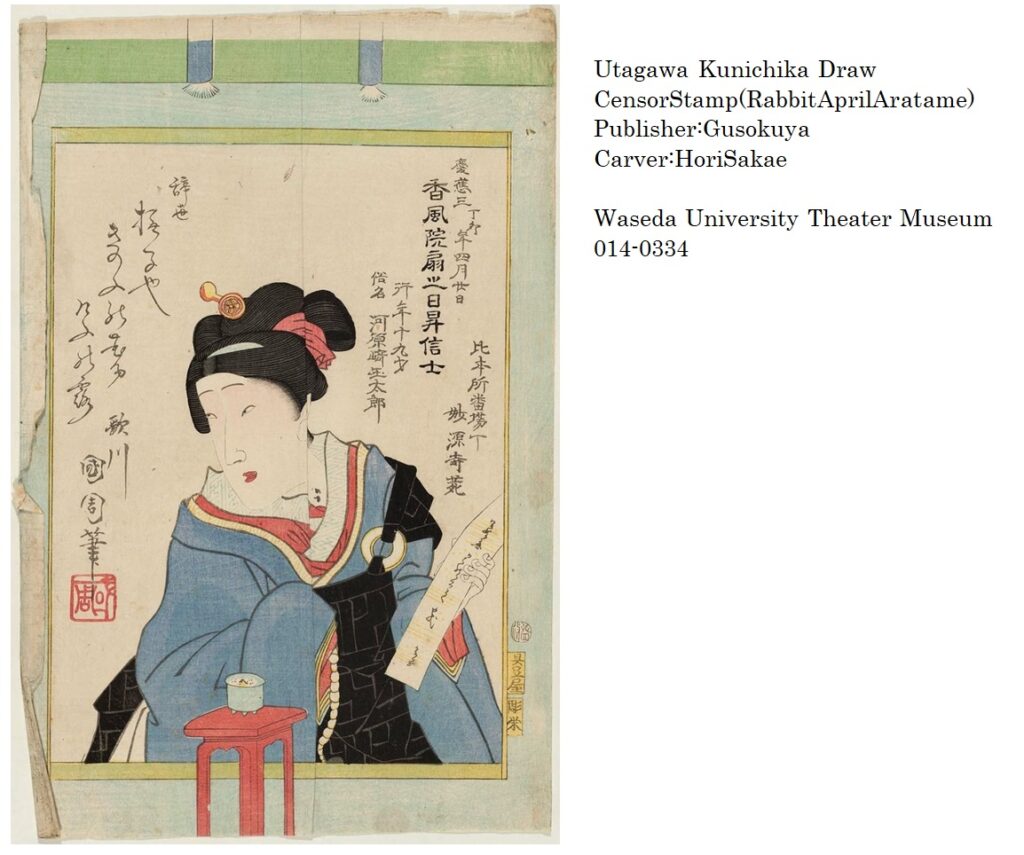

In 1869, he released Ohkao-e from Gusokuya, which was highly praised by many critics. This is a technique that is often used in modern film. By filling the screen with only the face, the viewer is completely blinded to the surrounding situation, and is forced to read the actor’s feelings from the actor’s facial expression. He used this technique to create masterpieces in which he transferred onto paper the feelings of kabuki actors, such as anger, doubt, anxiety, peace, and suspicion. He expressed a variety of emotions through subtle changes in the cheeks, eyebrows, mouth, and eyes. Until then, actor paintings had typically had slanted eyes, hooked noses, glaring and showing off, while portraits of beautiful women were generally deadpan. This suppressed expression of joy, anger, sorrow, and happiness was a traditional way of drawing that allowed the viewer to see the complex and subtle psychology of the protagonists(65). This matter will be discussed further in “3-6 The considerations of his Ukiyo-e works”. In addition, he first used the name Toyohara Kunichika in 1870; this will be discussed in the next section, “3-2 Changes in painter’s Name.”

3-2 Changes in painter’s names

Regarding the artist name, the origin of Toyohara Kunichika’s name and when he started using it are unclear. Kojima (1, p244) states that when he became a disciple, Toyokuni III gave him the artist name Ichiousai Kunichika. Furthermore, dictionaries and other sources state that he used names such as Ittou Kunichika一桃国周, Kachoro花蝶楼, Sokuroto曹玄人, Beiokina米翁, and Houshunrou豊春楼. Regarding the specific names he used, we looked at Kunichika’s early works (up to 1870) and chronologically show the changes in the various artist names he used in the following table.

As a result, in 1852, as pupil Yasohachi, he painted pictures under the name Koma-e for his master Toyokuni III. From 1853 to 1854, he produced works under the artist names Utagawa Kachoro歌川華蝶楼and Utagawa Kachoro歌川花蝶楼, but they do not bear the publisher’s stamp or censorship stamp. In 1854, he published “春景花遊図,” but this work was censored and the publisher was Shimizuya Naojiro, and the work bears the artist’s name “Kunichika国周” surrounded by a New Year’s stamp, which is considered to be his official debut work. In the field of illustrations, he debuted in 1855 with supplementary illustrations in “Oomisoka Akebono Zousi” as “Ichiousai一鶯齋”, and in 1856 he illustrated the entire “Yoshinaka Yusenroku” under the name “Utagawa Kunichika歌川国周”. He often used the names “Ichiousai一鶯齋”, “Ousai鶯齋”, “Kunichika国周”, “Chika知哥”, etc. In the field of ukiyo-e, he published works under the names “Ichiousai Kunichika”, “Ichiousai Kunichika”, “Ousai Kunichika”, and “Kunichika”. He became popular around 1863 and the number of prints published increased. Toyokuni III passed away in 1864. Around that time, from 1864 to 1870, the name Kunichika became mainstream, and the name Ichiousai Kunichika was rarely seen. The name Toyohara Kunichika was first used in January 1870, but many of the works that year still used the name Kunichika. The following year, 1871, the name Toyohara Kunichika was used in over 20% of the works, but many of the works were still signed by Kunichika. However, by 1872, the name Toyohara Kunichika was almost unified, and the number of works using only Kunichika’s name became very few. Between 1870 and 1871, the signature changed from Kunichika to Toyohara Kunichika. In “Toyohara Kunichika Den (Biography)” (1), Kojima Chosui wrote that he used the name Toyohara from 1871 (Meiji 4), but in fact he had been using the name “Toyohara Kunichika” since the previous year, 1870. He used other names in addition to those mentioned above. As summarized in the table, the art names that were used for a short period of time include “Chika知哥”, “Chika周”, “KachourouKunichika花蝶楼国周”, “Kachourou華蝶楼”, “MushunanKunichika霧春庵国周”, “Kunichika国ちか”, “Kunichiくにち”, “YanagisimaKunichika柳嶋国周”, “Ichiwousai一をう齋”, “Ittou Kunichika一桃国周”, “Ichibai Kunichika一梅国周”, “Kimimatsu Kunichika君松国周”, “Oukou Kunichika応好国周”, and “Ichitame Kunichika一為国周”. Hoshunrou豊春楼 (23),曹玄子,米翁(23), and other art names that are not listed in the following table may have been used after 1870.

The oldest work in which Kunichika used the name Toyohara Kunichika is from January 1970. There are several theories about when he started using the name Toyohara. Higuchi Hiroshi (82, p87) says that it was taken from one character each of the names of his two masters, Toyohara Chikanobu and Toyokuni III. There are several theories about the reason why he started using Toyohara as an artist surname. Theory 1: Watanabe Akira (79, p12) says, “Some people believe that the fact that Kunisada II took the name Toyokuni IV had some influence.” It is not clear whether Kunisada II became Toyokuni IV around 1870 or 1871, but it is roughly the same time that Kunichika started using the name Toyohara. Theory 2: Makuuchi Tatsuji (79, p171) says that on September 19, 1870, the Meiji government issued an order to allow commoners to use surnames. Therefore, the theory presented is that Kunichika began calling himself “Toyohara” in the leap October of that year, but this is thought to be a stretch, as he had been calling himself Toyohara for 10 months prior to the decree. A new way of thinking, but I think this timing may have been due to the seventh anniversary of the death of his master Toyokuni III. Kunichika was a Buddhist, as his grave is at Honryuji Temple, a temple of the Shinshu sect (46, p25). However, the annual memorial service is not a Buddhist teaching, but a custom. In the Nara period, the annual memorial service ended with the first anniversary, in the Heian period it was held up to the third anniversary, and in the Kamakura period it was held up to the 33rd anniversary, which became longer depending on the economic power. It is not clear when and how the memorial service for the common people as a memorial service for the deceased and ancestor worship began (66). After the 49th day memorial service, the mourning period ends and the soul of the deceased leaves the roof ridge (67). The 33rd anniversary is considered the end of mourning, and the deceased becomes a god. In addition, from the seventh day after the death to the 33rd anniversary, 13 Buddhas and Bodhisattvas are assigned to each day (68). From the above, the meaning of the 49th day and 33rd anniversary is clear, but it is not clear how the other 7th anniversary and others were understood in the cultural context of the time. However, the 7th and 13th anniversaries can be understood as a turning point that marks a turning point in feelings toward the deceased. Toyokuni III died in December 1864. If we count by the “counting age method” of the time, 7 years would have passed on New Year’s Day in 1870. Kunichika was brought up by Toyokuni III, the leader of the Utagawa school, and was given the name of Ichiousai Kunichika, so he was reluctant to use the name Toyohara of his previous master, Toyohara Chikanobu. So, it is likely that he began to use the name Toyohara Kunichika after the 7th anniversary of his master’s death. Moreover, it is understood that he did not change his name all at once, but rather over a period of about two years from 1870 to 1871.

When searching for Ukiyo-e, works from before 1870 using the name Toyohara Kunichika turn up, but there are no works that can be determined to be from before 1870 with certainty due to the following errors in judgment. The reasons for the errors were (a) misreading of the censorship stamp, (b) the position of the actor was vacant at that time, so there was no actor who fit the name, or (c) the play was written after 1870. Details were discussed in Chapter 1.

Regarding the artist surname “Utagawa,” in the field of illustrations, he used the name Utagawa Kunichika in his debut work “Yoshinaka Yusenroku” in 1856. The next time Utagawa Kunichika was used was in 1863 for “Mizukagami Yamadori Kitan” and “Karimakura Tatsumi Hakkei,” and he is not used very often in the field of illustrations either. The only ukiyo-e work that bears the name Utagawa Kunichika can be found in the memorial painting of Kawarazaki Tamataro from 1867, but I have yet to see any other examples of this being used in so-called ukiyo-e or actor paintings. This memorial painting of Kawarazaki Tamataro has the name Utagawa Kunichika written on it and Kunichika’s seal stamped on it. It is interesting why the name Utagawa Kunichika was only used for this memorial painting. In this way, it can be said that Kunichika never called himself “Utagawa” in the field of ukiyo-e, but rather that he rarely used the name.

Finally, regarding the use of the term “disciple,” there are three works in which Kunichika bears the name “disciple Kunichika.” In 1855, in “Sumidagawa Yowatashi no zu,” he called himself “Disciple Kunichika,” and in 1856, in “Shunsen 12ji,” he called himself “Disciple Kunichika.” After that, there were no works with “Disciple Kunichika” written on them for a while, and in 1864, in a memorial painting for Toyokuni III, he called himself “Disciple Ichiousai Kunichika” as a sign of respect. Regarding when Kunichika became independent, I focused on the presence or absence of “disciple.” As described in Chapter 2, 1852, I thought that even if he painted a picture in the background of Toyokuni III, the meaning would be different if he wrote “Disciple Kunimori” or “Hiroshige.” Artists who were already independent would have written only the name “Hiroshige” as a collaborator, and if they were still in training, they would have written “Disciple Kunimori.” From these facts, it is believed that he became independent around 1856.

1852 Takiyasha, Toyokuni III, Disciple Yasohachi

1853 Empress Jingu, Toyokuni III, Disciple Yasohachi

1854 Harunokei Hanaasobi zu, Kunichika

1855 Sumidagawa yowatasi no zu, Kunichika, Toyokuni’s Disciple Kunichika All of this triptych was painted by Kunichika, but in honor of Toyokuni, he is listed as a Toyokuni’s Disciple.

1856 Shunsen 12ji, Disciple Kunichika Kunichika painted koma-e

1857 Asakusa Sanchuu Hanakurabe, the background by Kunichika Although he painted the backgrounds for Toyokuni III’s paintings, he is not listed as a disciple, but as an independent artist and the works are recognized as collaborative works.

1864 Memorial painting of Toyokuni III: Disciple Ichiousai Kunichika The meaning of “disciple” here is a sign of respect for the master.

.

Kunichika:Change of picture’s name

Kunichika:Change of picture’s name

| Year | Signature of Kusazoshi | Signature of Uchiwa-e | Number found in “Ukiyo-e search” & Ukiyo-e and its Signature |

| 1852 | One work is open to public. 滝夜叉(門人八十八) Yasohachi | ||

| 1853 | One work is open to public. 神功皇后(門人八十八) Yasohachi | ||

| 1853 ~ 1854 | Four works are open to public 大口屋内花遊 歌川花蝶楼 端午の節句 歌川華蝶楼 重陽の節句 歌川華蝶楼 七夕 歌川華蝶楼 Utagawa kachourou | ||

| 1854 | One work is open to public. 春の景花遊図(国周) Kunichika | ||

| 1855 | 大晦日曙草子(一鶯齋) Ichiousai | Two works are open to public. 隅田川夜渡之図(豊国門人国周,国周 ) 源平八島大合戦 華蝶楼画 Kunichika, Kachourou | |

| 1856 | 義仲勇戦録(歌川国周) 頼朝一代記上巻 国周画 八犬伝 犬の草子(知哥) 題大磯虎之巻筆(知哥,周) 三世相縁の緒車( 国周) 安政見聞誌(一鶯齋国周) 四家怪談(一鶯齋) 和漢武者鏡(国周) Utagawa Kunichika, Kunichika, Chika, Ichiousai Kunichika, Ichiousai | One work is open to public. 春選十二時 酉の刻(門人国周) Kunichika | |

| 1857 | 鼠小紋東君新形(国周,一鶯齋) 当南見延御利益(一鶯齋国周) 伊賀の仇討(国周) 頼朝義経一代記(国周) 北雪美談時代加々見(一鶯齋) 頼光大江山入(国周) 白石物語(国周, 一鶯齋国周) 河中嶋烈戦後記 後編上巻(歌川国周) Kunichika, Ichiousai, Ichiousai Kunichika, Utagawa Kunichika | Four works are open to public. 浅草山花くらべ(国周) 今様源氏之内月(一鶯齋国周, 花蝶楼国周,国周) 十二ケ月之内正月大川通(一鶯齋国周) 十二ヶ月之内灌仏会(花蝶楼国周) Kunichika,Ichiousai Kunichika, Kachourou Kunichika | |

| 1858 | かちかち山(一鶯齋国周, 国周 ) 新増補西国奇談(国周, くにち) 伊賀越仇討(一鶯齋国周) 教草朝顔物語(国周) Ichiousai Kunichika, Kunichika, kunichi | Thirteen works are open to public. 虹が嶽( 一鶯齋国周) 松ヶ枝 ( 国周) 鷲が浜( 一鶯齋国周) 当世美人揃( 一鶯齋国周, 国周) 浅草金龍山市之図(国周,花蝶楼国周, 一鶯齋国周) 養蚕( 一鶯齋国周) 悪七兵衛景清他( 一鶯齋国周, 国周) 源氏五節句之内七夕 (国周) 風流見立福づくし( 一鶯齋国周, 国周) 目一秘曲平家一類顕図( 華蝶楼) 相馬良門古寺之図 ( 国周) 当世美人揃霞ヶ関夕照(一鶯齋国周、国周) 尾上勘兵衛 (花蝶楼国知哥) Ichiousai Kunichika, Kunichika, Kachourou Kunichika | |

| 1859 | 報讐信太森( 一鶯齋国周) 英雄成生功記(一鶯齋国周) Ichiousai Kunichika | Three works are open to public. 笠松峠鬼人を討取図(国周) 安宅の関勧進帳 ( 国周) 花盛美人揃( 国周, 一鶯齋国周) Kunichika, Ichiousai kunichika | |

| 1860 | Ten works are open to public. 花盛美人揃再版(国周) 文治四年摂州大物浦灘風之図(国周, 一鶯齋国周, 露松庵国周) 今様源氏三曲遊興之図( 国周) はちかんじひさみのてこまえ(一鶯齋国周) 今様福神宝遊狂( 一鶯齋国周, 国周) 山王御祭礼番付( 国周) 太平記大合戦(一鶯齋国周) 横浜廊中(花蝶楼国周、一鶯齋国周) 大井川徒行渡図(国周) 重岡(国周) Ichiousai Kunichika, Kachourou kunichika, Kunichika, Roshouan Kunichika | ||

| 1861 | 教草女房形気(一鶯齋) 濡衣女鳴神(歌川国周, 国周,一為齋国周) Ichiousai, Utagawa Kunichika, Ichitamesai Kunichika, Kunichika | Eleven works are open to public. 木性の人( 一鶯齋国周) 福人寿有卦入船( 国周) 丁卯二月七日金性の人うけニ入( 一鶯齋国周) 水性の人八月五日うけに入(一鶯齋国周) 太平記(国周) 忠臣義士仇討(国周、一鶯齋国周、一鶯国周) 蛍遊び(華蝶楼国周、一鶯齋国周) 河原崎権十郎 (国周) 滝川・長尾・中川(一鶯齋国周画、国周) 長尾・重岡・花紫 (国周) 田毎(国周) Ichiousai Kunichika, Kunichika, Kachourou Kunichika | |

| 1862 | 梅春霞引始(国周, 国ちか) Kunichika, | Two prints 国周 | Ninety-two works are open to public. 南総里見八犬伝(柳嶋国周、国周、一鶯齋国周) 、一鶯齋狂画など “Yanagisima Kunichika”, “Ichiousai Kunichika”, “Ichiou Kunichika”, “Ichiousai Kyouga” and “Ousai Kunichika” are used, but about 85% or more use “Kunichika”. |

| 1863 | 水鏡山鳥竒譚(国周, 歌川国周,一鶯齋国周) 假枕巽八景( 国周, 歌川国周,一鶯齋国周) 義勇八犬伝( 国周) 金花七変化(くにちか,一をう斎) Kunichika, Utagawa Kunichika, Ichiousai Kunichika, ichiousai | Two prints 国周 一桃国周 | Two hundred and seventy-nine works are open to public. 宅開酒宴之図(応需国周, 国周) 沢村田之助 (一桃国周) 源氏の若近江八景(一桃国周,国周) 其田練廓里暁(一梅国周、国周) そのゆかり源氏寿古六(一鶯齋国周) 蒙古襲来(応需国周) Ouju Kunichika, Itto Kunichika, Ichibai Kunichika, Ichiousai Kunichika. Others Approximately 70% is Kunichika(国周) |

| 1864 | 水鏡山鳥竒譚(一鶯齋, 国周) Ichiousai Kunichika | Seven prints 国周 | A total of 410 works are open to public. 豊国III追善絵(門人一鶯齋国周) There are several signatures of一鶯国周(Ichiou Kunichika) and一鶯齋国周(Ichiousai Kunichika). The other 99% is Kunichika(国周). |

| 1865 | Thirteen prints 国周 | A total of 633 works are open to public. 6 works by一鶯齋国周(Ichiousai Kunichika), 99% of the others are Kunichika(国周) | |

| 1866 | 花暦封じ文(一鶯齋国周) Ichiousai Kunichika | Five hundred and forty-two works are open to public. 一鶯齋国周(Ichiousai Kunichi’s) signature is 3 prints (actually 2 works). The other 99% is Kunichika(国周). | |

| 1867 | 和可紫小町文章(国周) Kunichika | A total of 1072 works (including year determination errors and other ukiyo-e artists) are open to public. Ichiousai Kunichika(一鶯齋国周) has 12 prints, Utagawa Kunichika (歌川国周)has 2 prints (same work), 99% of the others are Kunichika(国周). | |

| 1868 | Three hundred and forty-nine works are open to public. Ichiusai Kunichika(一鶯齋国周), Ichiou Kunichika(一鶯国周), Ouju Kunichika(応需国周), and Oukou Kunichika(好応国周) have one work each, and the rest are all Kunichika(国周). | ||

| 1869 | One hundred and ninety works are open to public. Ichiousai Kunichika(一鶯齋国周), Ouju Kunichika(応需国周), and Kimimatsu Kunichika(君松国周) have 1 print each, and the rest are all Kunichika(国周). | ||

| 1870 | Three hundred and twenty-seven works are open to public. Most of them use the name of Kunichika(国周). The name Toyohara Kunichika(豊原国周) has been in use since January, and about 13 works have been published. | ||

| 1871 | A total of 223 works are open to public. Toyohara Kunichika’s signature (豊原国周)is about 20% of the total, and most of the others are Kunichika’s signature(国周). | ||

| 1872 | A total of 298 works are open to public. Almost all signed by Toyohara Kunichika(豊原国周) |

.

3-3 Toshidama Stamp, Gohishi Stamp, Rakkan

A Tosidama Stamp is a round seal stamped under the words “Kunichika painting” on an ukiyo-e print, and its impression resembles a stylized crest of the Utagawa school. Sometime this round mark becomes an elongated oval with a name written inside it. Kunichika also used this Tosidama Stamp to show that he belonged to the Utagawa school.

.

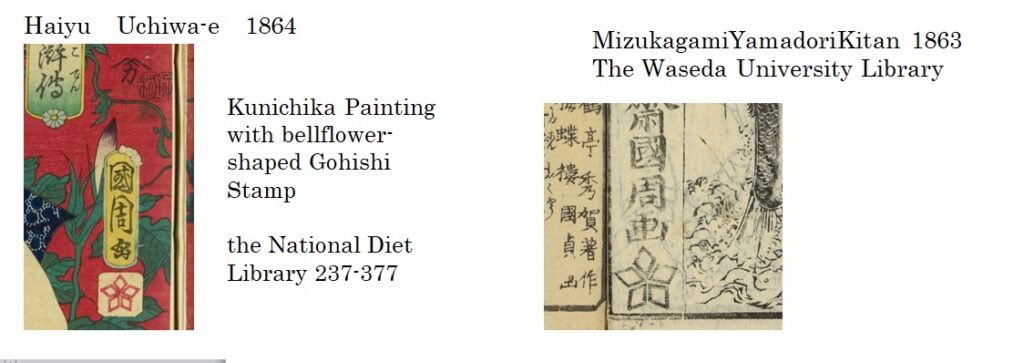

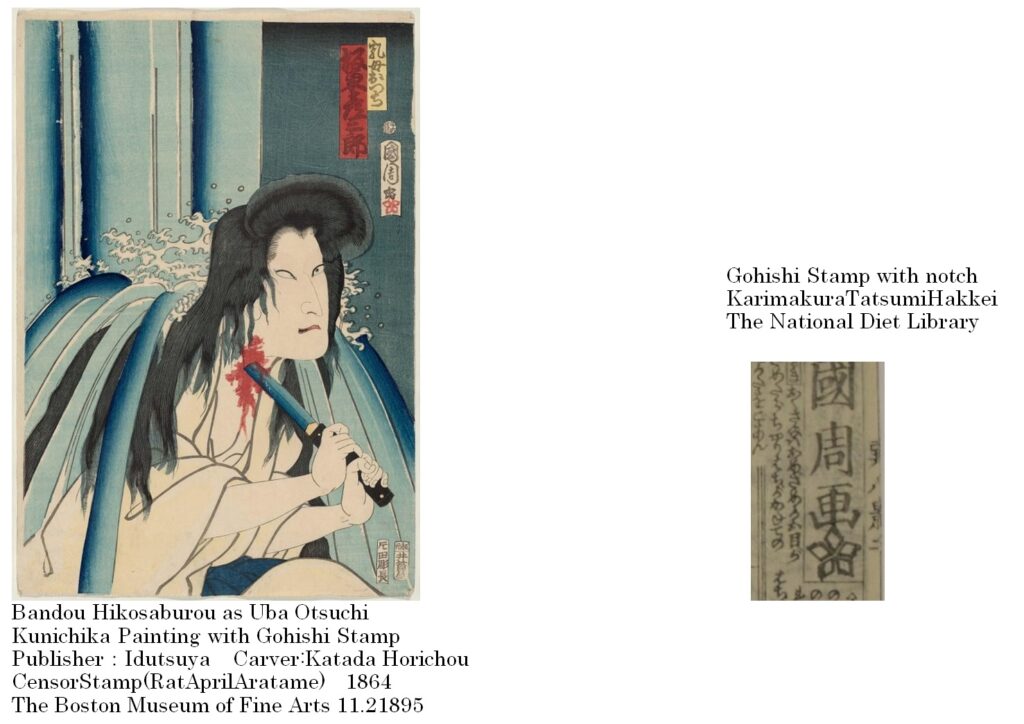

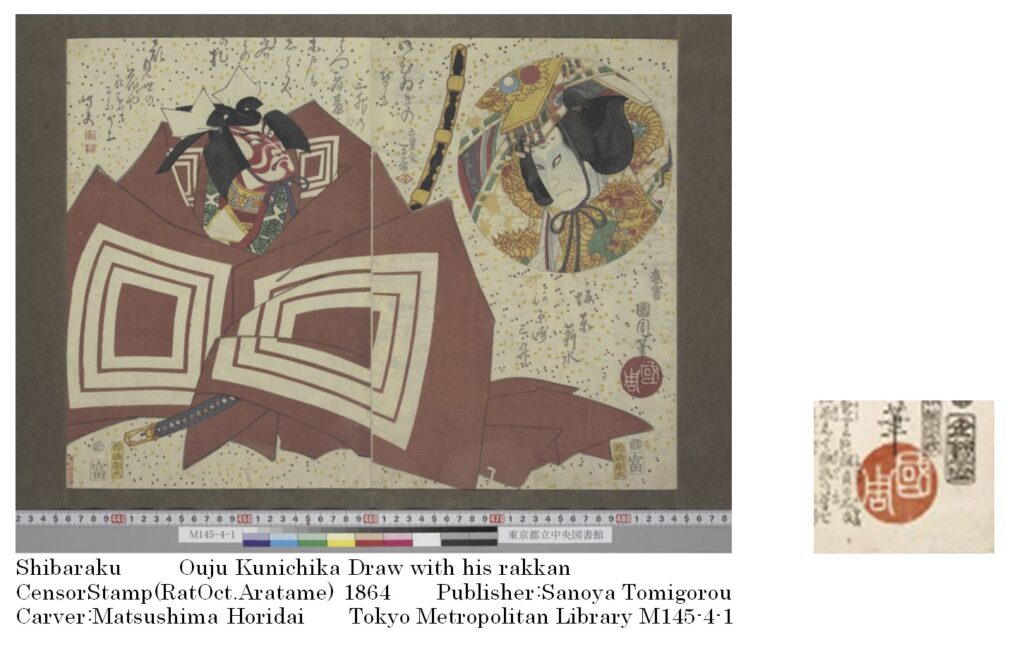

The next example is from “Horimono Suikoden” (fan painting) in 1864. This is an example of the Tosidama Stamp with the words “Kunichika Painting” written inside, which is also commonly used. In this “Horimono Suikoden”, the Gohishi Stamp was stamped further below. The diamonds are drawn with straight lines. The oldest example of this Gohishi stamp is from 1861, when it was stamped on “Mokusei no Hito August 5th Ukenihairu”. Another example is the Gohishi stamp used in the 1863 Kusazoshi “Mizukagami Yamadori Kitan”. In a work depicting Bando Hikosaburo in 1864, part of the diamond is notched, and the whole shape looks like a cherry blossom. Or, the notched part of the diamond looks like a bumpy shape in the upper right corner of the Tosidama Stamp. A similar example is the stamp used on the 1863 kusazoshi “Karimakura Tatsumi Hakkei.” There is no clear relationship between the time of use of these two types of Gohishi stamps, and they do not appear to have been intentionally differentiated. This five-diamond seal was used for a short period from 1861 to 1864. In 1861, Kunichika got married (79). This was also the time when the number of works began to increase, and he began to feel confident because “someone said that my paintings were better than those of my master” (17). He may have suddenly dreamed of independence like Kuniyoshi, but when his master Toyokuni III died in 1864, he stopped using this seal. It would be good if some kind of record remained, but for now, the purpose of using this five-diamond seal is unknown. Another point to consider when estimating Kunichika’s intention is that the five-diamond seal is stamped on the inscription “Otosin Fude” on a folding screen of paintings by “Sawamura Tanosuke, Sawamura Tosshou, Nakamura Shikan” from 1864. This five-diamond seal was used for a short period from 1861 to 1864, and was not used after Toyokuni III died.

Kunichika’s master Kunisada also used a stamp with an inscription on the crest to create the image of a Tosidama stamp. The second and fourth volumes of Nuregoromo Onnanarukami, published in 1856, have a stamp with “Drawing by Ichijusai Kunisada” and an inscription on the upper right of the three-tiered diamond. The third and fourth volumes of Nuregoromo Narukami, published in 1858, also have a stamp with “Drawing by Utagawa Kunisada” and an inscription on the three-tiered diamond. Kunichika was obviously aware of the use of inscriptions like this to create the image of a Tosidama stamp.

The next example is a use of a Rakkan with “Kunichika” written in seal carving. The oldest example is from 1858 in the eighth volume of Kusazoshi “Osiegusa Asagao Monogatari”. It can be seen in the memorial paintings of his master Toyokuni III and “Shibaraku” in 1864, but there are few examples of its use.

3-4 Landscape paintings

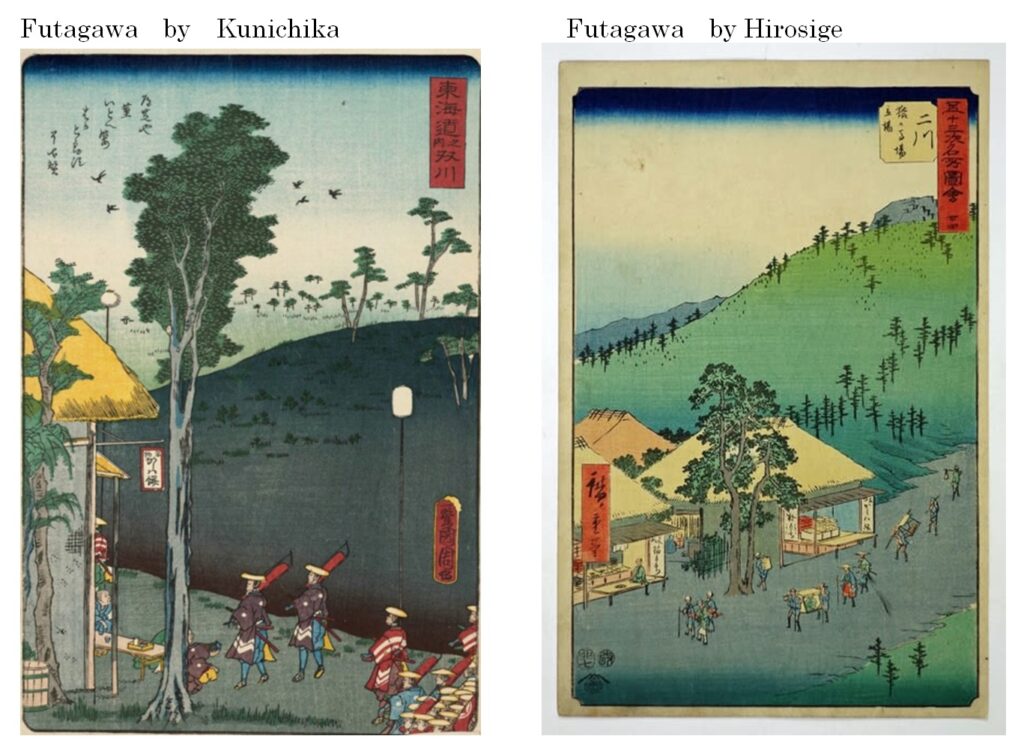

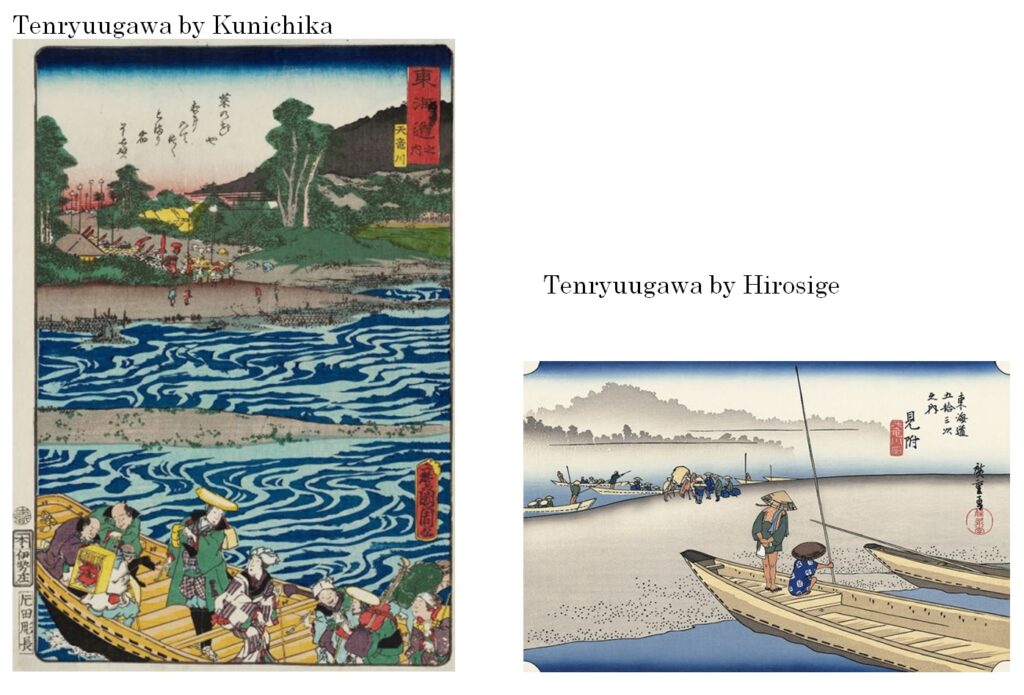

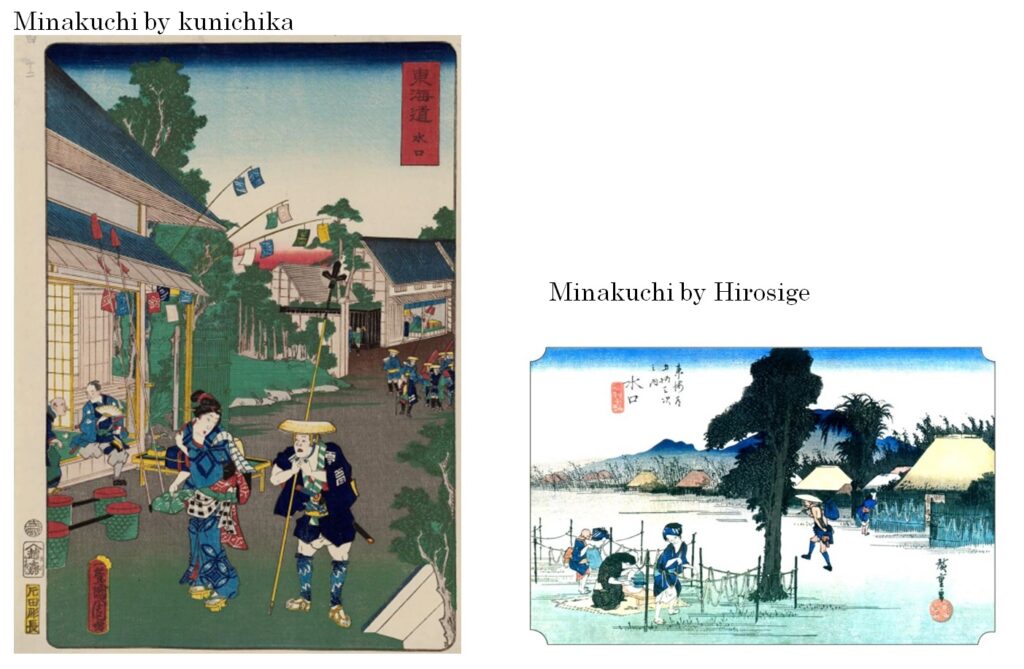

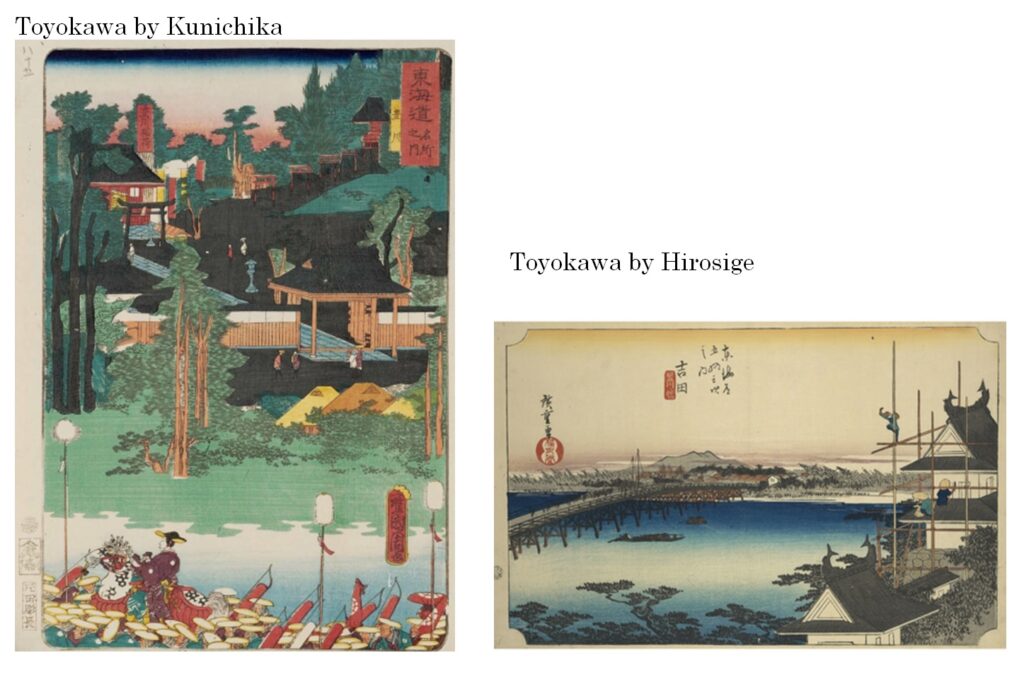

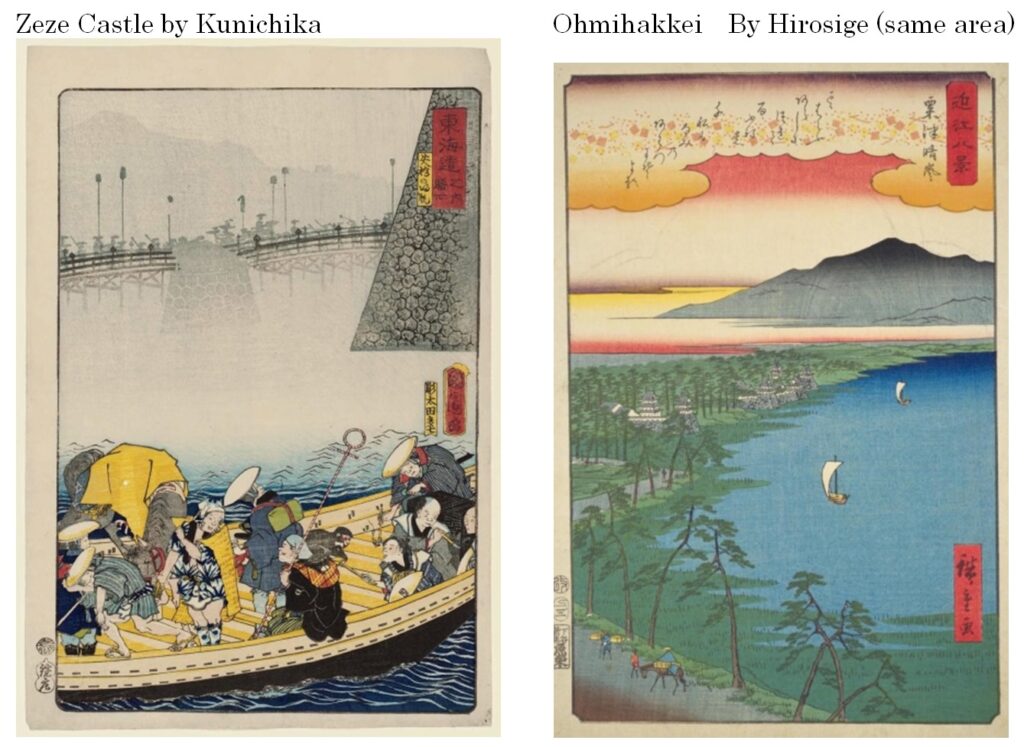

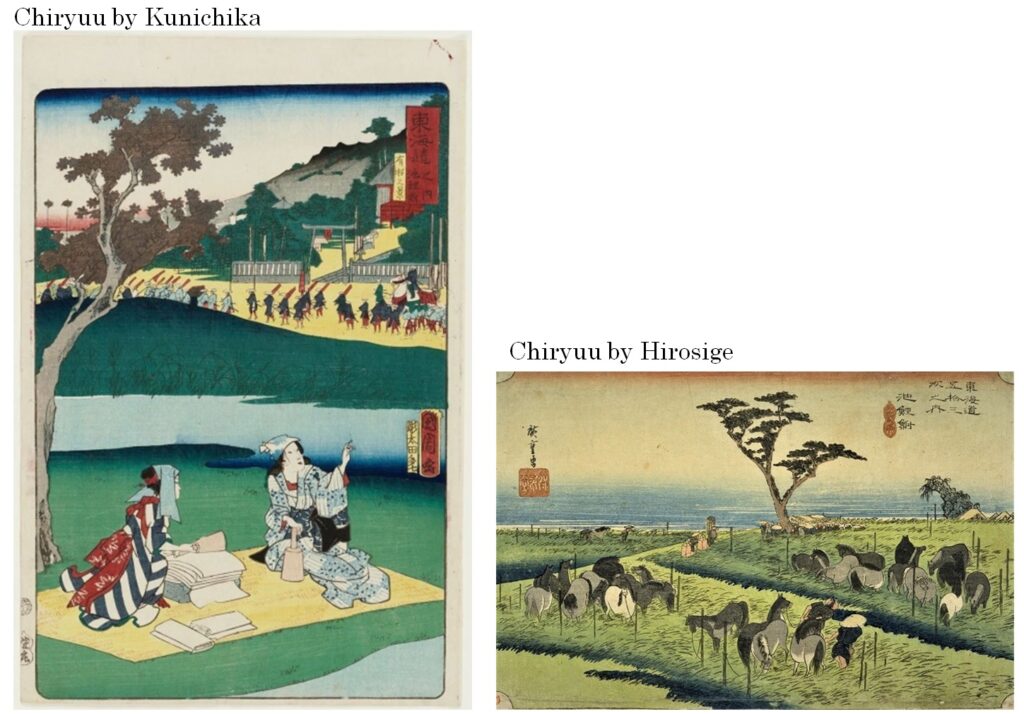

As for landscape paintings, Hokusai, who painted landscapes with dynamic emphasis, and Hiroshige, who painted landscapes that captured nature and the travel atmosphere of the land, left behind wonderful works. The subject of a landscape painting is the landscape, not the person. Therefore, a painting with one or two people and a certain action as the subject is not a landscape painting. With such a composition, attention is drawn to the person’s actions before the natural scenery or the townscape. If the painting contains people passing by or small people, it is understood as part of the landscape. Looking at Kunichika’s works from this perspective, a landscape painting that fits this definition appears in 1863, but none were found outside of that year. Most of Hokusai and Hiroshige’s works are horizontal, but all six of Kunichika’s works are painted in the same vertical screen as actor paintings. In this screen, perspective is emphasized rather than horizontal expanse, allowing both close and distant situations to be expressed. However, when using this vertical screen as a landscape painting, it generally becomes distracting unless it is painted with the same theme as a hanging scroll.

This landscape painting was part of a series called Gojouraku Tokaido. It was part of a group of works that Toyokuni III shared with 16 Utagawa school artists, and was intended to celebrate the first event in 229 years, Tokugawa Iemochi’s visit to Kyoto (57, 58). The total number of works was 162, but as is clear from Kunichika’s painting, there was no uniformity in the titles, with many different themes such as “Tokaido no uchi xxx”, “Tokaido meisho xxx”, and “Tokaido xxx”. Each work was published in turn as a series, and eventually became a set of books. It was Toyokuni III who gathered the Utagawa school artists and took charge of the production, and he had overall responsibility above that of a publisher. (All of this is from Yamamoto Noriko (59)). Therefore, although it is a landscape painting, it is thought that Toyokuni III, who was in charge of the production, instructed that the warrior procession be treated as part of the landscape and that it be composed vertically.

Kunichika’s Tenryu River, Toyokawa River, and Zeze Castle works are like this hanging scroll style. In the “Mizuguchi” painting, the focus is on the people rather than the landscape. As a result, he was unable to paint a dynamic landscape like Hokusai or a travelling mood like Hiroshige. In “Nikawa,” both Kunichika and Hiroshige paint vertically, and it seems like a place that can only be expressed by including a distant view, as it is deep in the mountains. In “Tenryu River,” Kunichika paints the Tenryu River flowing violently in the torrential rains of the rainy season, but Hiroshige paints the spaciousness of the dried-up Tenryu River. As expected of Hiroshige, he turns a landscape that is not picturesque into a picture of travelling mood. As for the “Toyokawa” painting, Kunichika paints it vertically, and includes Toyokawa Inari in the background, making it an impressive hanging scroll-like painting. Hiroshige paints a spacious landscape with a sense of perspective by painting it horizontally. These two paintings show a big difference between the vertical and horizontal positions of the composition, and Kunichika makes good use of the characteristics of the vertical position. However, the next work, “Zose Castle,” seems to be an example in which this shortcoming is particularly evident. Kunichika’s “Zose Castle” seems to focus on the passengers on the ship, but the depiction is incomplete and the stone wall in the upper right corner is abrupt. Hiroshige completed his work with the Eight Views of Omi, which included a landscape that resembled Zeze Castle. Okubo Junichi (26, p. 65) states that Kuniyoshi was actively painting landscapes around 1840, but the small number of paintings in storage indicates that he was not successful. The field of landscape painting that Hokusai and Hiroshige created seems to have been overwhelmingly influenced by their works.

There is a painting at the British Museum that is listed as a work by Kunichika. Among them is a large horizontal painting that is connected vertically, and looks like a hanging scroll. Since it is a rough sketch, the signature and date are unknown, but Ms. Rosina Buckland of the British Museum reported to me that “The drawings were attributed to Kunichika based on stylistic analysis. If they were preparatory drawings, one would not expect them to have a signature.” It is unclear when the painting was done, and judging from the face of the person depicted, it may have been a work from his later years, but I cannot be sure that it is Kunichika’s work. However, when I look at Kunichika’s landscape paintings, I think the composition is also Kunichika’s work. It is a painting that makes use of the characteristics of a vertical composition. There is no certainty that it is Kunichika’s work, but if it was Kunichika who painted it, if we know what year it was painted, we may be able to infer what Kunichika was thinking.

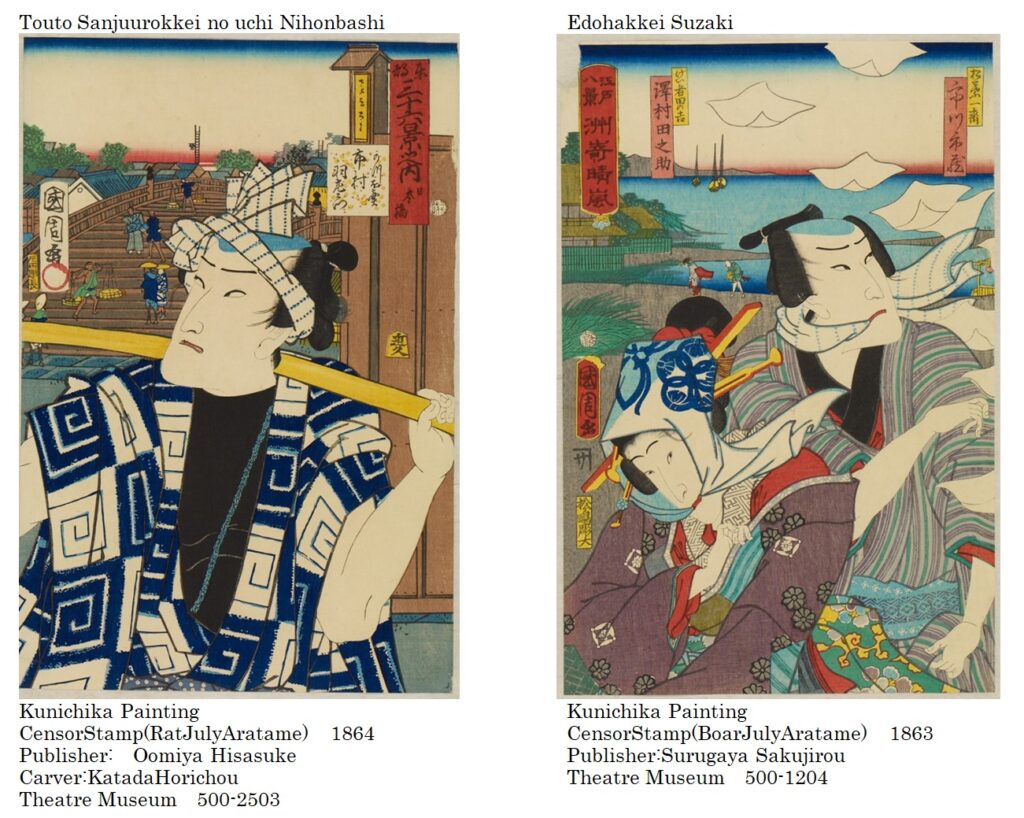

Kunichika did not produce any more works that could be acclaimed as landscape paintings, but he did leave behind some excellent landscapes in the backgrounds of his actor paintings from this time, such as Edohakkei Suzaki Harekaze(1863) and Touto Sanjuurokkei no uchi Nihonbashi (1864).

The following landscapes are in the collection of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

.

The following paintings are two works that the British Museum attributed to Kunichika. Since the subject appears to be a person, it cannot be called a landscape painting, but rather has the same impression and composition as Kunichika’s landscape paintings.

.

3-5 Establishment of actor face paintings

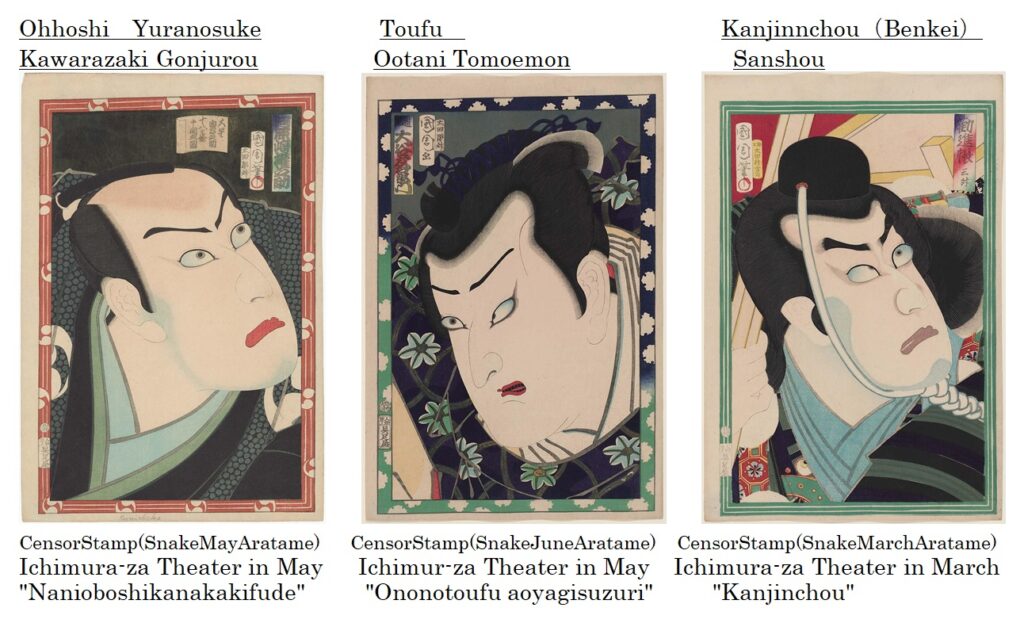

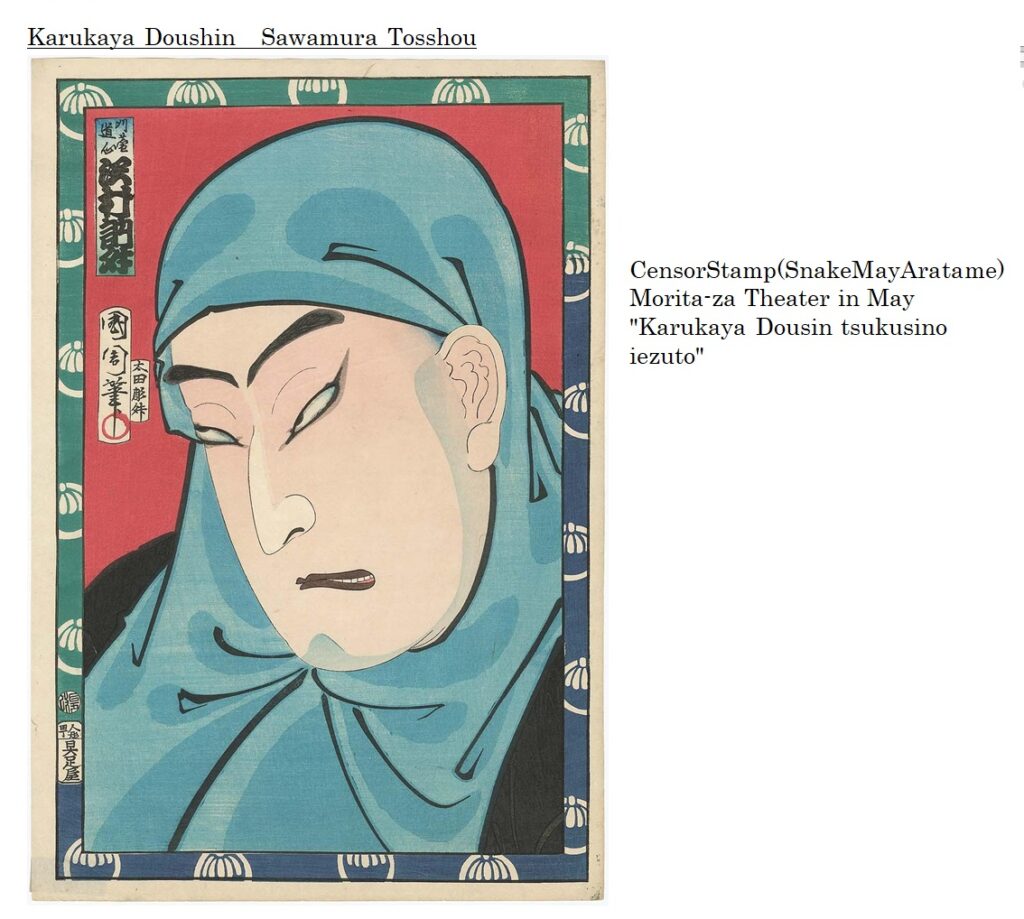

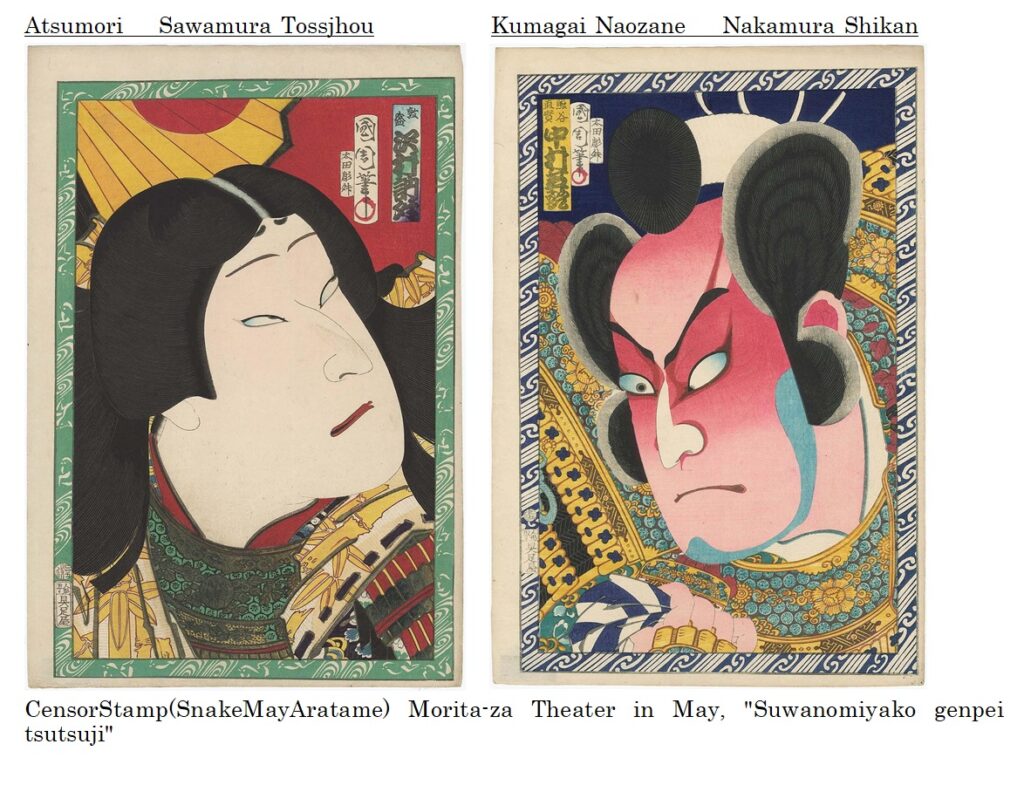

Kunichika’s first Kabuki actor painting was the 1859 work “Ataka no Seki Kanjincho” with an unclear signature. Kunichika seems to have used Toyokuni III’s woodblock to create a work that appears to have repainted and recarved only the face of Togashi no Suke Iemori (Otani Tomoemon). Until then, Kunichika had painted many characters in Kusazoshi, but he painted them not as actors, but as ordinary people. As can be seen from the characters that appear in Yotsuya Kaidan from 1856, the faces are diverse. This was the first time Kunichika painted the faces of actors, but comparing Toyokuni III and Kunichika, there is a difference in the facial expressions, and Kunichika’s paintings have a gentler feel. It is thought that the faces of actors were required to match the image of popular actors that theater lovers had. It is thought that Kunichika first asked the people of Edo about actor paintings in his own style. Also, since the face of this Otani Tomoemon is similar to that of subsequent Otani Tomoemons, it is thought that he grasped his features and then began to draw the ideal face of a popular actor. After that, Kunichika’s first signed actor painting was thought to be a work of Kawarazaki Gonjuro in 1861 (see Chapter 2, 1861). The facial expression of Kawarazaki Gonjuro in this painting is different from the facial expressions of ordinary people that he painted in Yotsuya Kaidan and other works, and depicts the face of a character wearing makeup who appears in a Kabuki play. This is probably the ideal actor painting that the people of Edo imagined. From 1862, the number of Kunichika’s works began to increase rapidly. It is believed that Kunichika’s painting of Kawarazaki Gonjuro in 1861 was the catalyst for the popularity of his work.

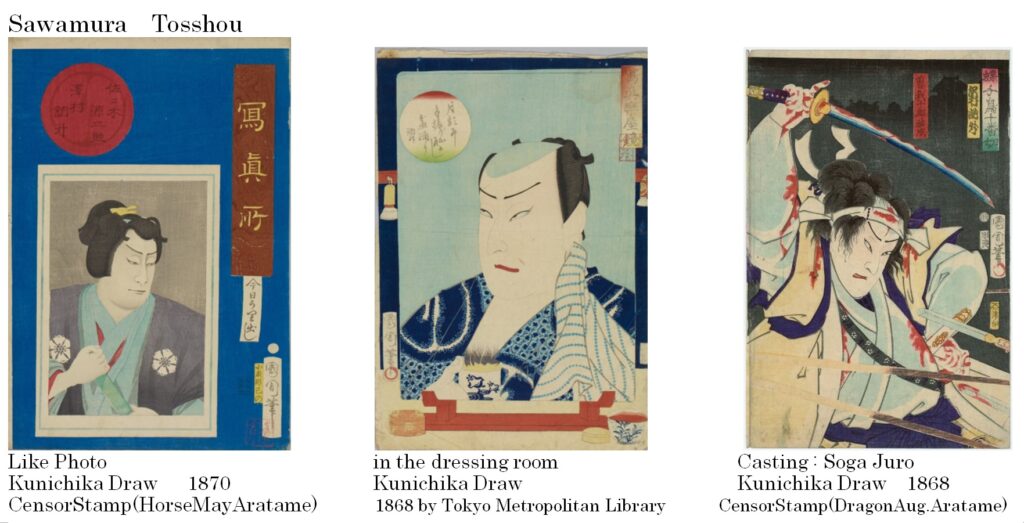

What was the ideal face of an actor that Edo commoners had in mind, according to Kunichika’s drawings? There is no painting of Kawarazaki Gonjuro, but there are three works by Kunichika depicting Sawamura Tosshou, which were compared and examined to see the difference between the actor’s real face and the face of the actor playing the role. The following illustration on the left (photo) depicts Tosshou in real life, just like the photograph, the illustration in the center (in the dressing room) depicts Tosshou relaxing in his dressing room, and the illustration on the right (role of Soga Juro) depicts Tosshou performing a fight scene in a play. These three were painted by Kunichika in 1868 and 1870. Comparing these three, the illustration on the left (photo) depicts the real image as a photograph, and Sawamura Tosshou’s eyes seem to have bulging upper eyelids, his nose is wide, and his chin is wide and sturdy. However, the face of Sawamura Tosshou (right: Soga Juro) playing the role is drawn with clear eyes, a long face, a thin chin and a straight nose. The picture of Sawamura Tosshou relaxing in his dressing room (center: in the central dressing room) is skillfully drawn somewhere between the face of the actor in the play and his real face. It is thought that Kunichika created the ideal face of the actor to play the role after capturing the characteristics of the actor. Therefore, I think that the actor portrait of Kawarazaki Gonjuro from 1861 introduced earlier was the first work in which the ideal actor portrait was completed using this technique. The following year, in 1862, he published works by Sawamura Tanosuke, Iwai Kumesaburo and others, and it is likely that Kunichika had perfected this technique for drawing actors’ faces around this time. It is thought that this was the background to his popularity as an ukiyo-e artist, and that the number of ukiyo-e prints he produced increased from 1863 onwards.

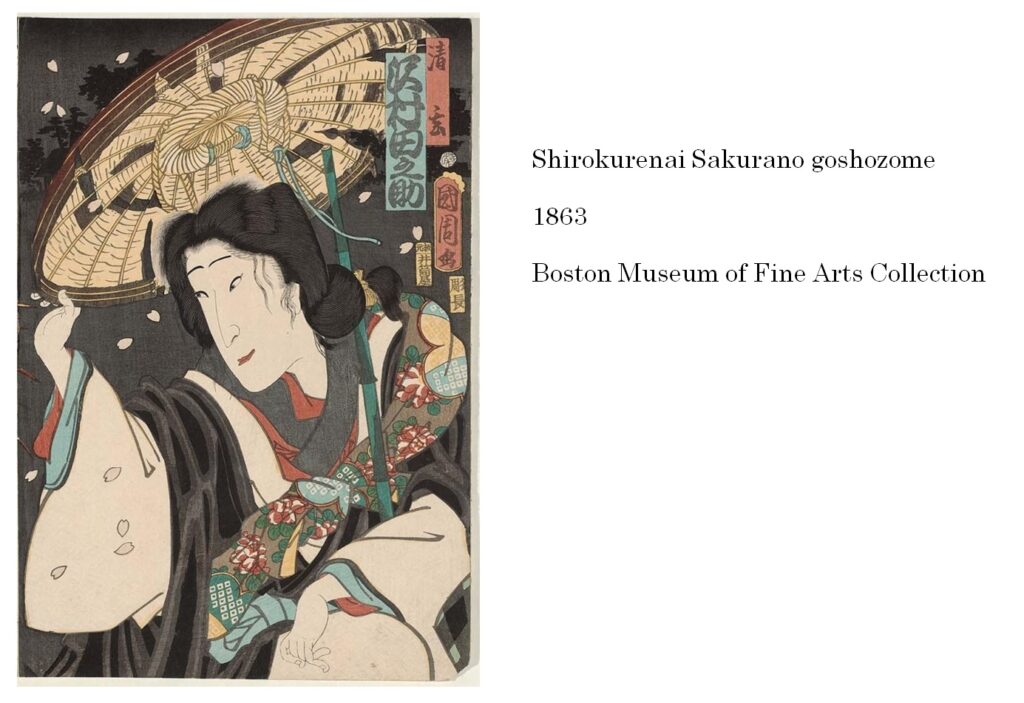

Specifically, Sawamura Tanosuke in Shirokurenai Sakurano goshozome from 1863, which was produced after Kawarazaki Gonjuro’s work from 1861, is depicted as a gentle and cute woman. In Kawarazaki Kunitaro and others, from 1867, five actors are depicted with gentle and cute faces typical of Kunichika, and although they look similar, each actor’s individuality is also apparent. For these reasons, Kunichika’s actor painting of Kawarazaki Gonjuro from 1861 was an important starting point.

3-6 The composition of his Ukiyo-e works

Many ukiyo-e artists recreated famous scenes from kabuki plays, portraying the moment’s appearance, glaring, and so on. However, Kunichika depicted the fun of Kabuki plays, the plot, and the facial expressions of the actors who expressed the sadness and anguish of the characters. He of course also painted impressive scenes like many ukiyo-e artists and pictures like bromides. The works that were highly evaluated for their drawing style and content were works that depicted a single actor on a triptych and big close-up works. In addition, since the facial expressions were drawn richly, the pictures were drawn so that the story could be understood by looking at the picture. In order to understand these characteristics, his ukiyo-e painting style was categorized and evaluated from the perspective of contemporary filmmaking.

In order to convey the Kabuki play to ordinary people, Kunichika captured the Kabuki play as an image and drew pictures in a way such as drawing the whole body and drawing from the waist up. The method of drawing seemed to be the same idea as today’s video production for movies and television. It’s a technique that’s still used by filmmakers today, but the terminology isn’t fixed. Here, the terms used in Hans P. Bacher’s “Vision Story Telling: Color, Light, Composition, Shot Size”(27,p184) are used. The angle of view (aspect ratio) differs depending on whether the work is a large paper, two large papers, or three large papers (Triptych). Furthermore, the content conveyed to the viewer will differ depending on whether the background is drawn or omitted. Ukiyo-e depicting people were classified into six categories based on the combination of how the people were drawn and the number of sheets of paper (screen size) used, and the characteristics of each were examined.

3-6A) Long shot

A long shot that shows the whole body of a person as if seen from a distance. By depicting the stage as seen from the audience, information such as the location of the story and the movements of supporting characters are conveyed, making the plot of the play clear. In this case, a lot of information can be depicted in a large triptych. There are examples of diptychs, but in this case it is a painting that requires careful consideration and close inspection. Even in a large triptych, each sheet is drawn so that it can be appreciated independently, but the edges of the kimono and sword of the person next to it and the stage background are drawn in succession to show that the works are connected. In principle, the whole body of the person is drawn whether standing or sitting.

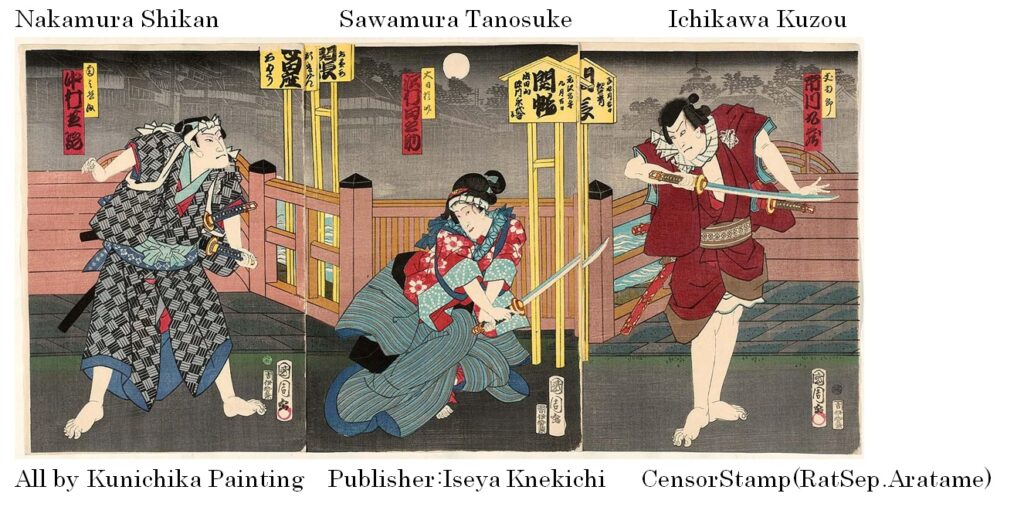

“Souma Yoshikado Furudera no zu” (1858) has a story written into the painting, so the story can be understood just by looking at it. In this case, in addition to the story of each individual character, the story is depicted through the related people around them and the objects drawn in the background. He has introduced expressive, ordinary people into the world of ukiyo-e, which is represented by beautiful women and landscape paintings, and there is an impression that he has brought a story in which several of them are talking about various things on their own. When it comes to the painting “Souma Yoshikado Furudera no zu,” many people know the story and will recognize it as a scene of Takiyashachihime demonstrating her magic to Souma Yosikado. The pictures are painted in such a way that the viewer can understand the story even if they know nothing at all. Futatsuchou Ironodekiaki (1864) depicts the entire stage in a long shot, and in the painting featuring Nakamura Shikan, Sawamura Tanosuke, and Ichikawa Kuzo, Tanosuke is about to take revenge on his enemy, but with a limp figure and the gestures of a weak woman, which Kunichika has skillfully depicted. The viewer is worried and sympathetic, thinking that she will never be able to take revenge. This cannot be depicted with a composition only from the waist up. Emotions can be read from each of the movements. Their facial expressions are not just for show or glaring, but each one expresses their intentions and tells a story. In this way, the depicted conversation conveys the story to the viewer, and the viewer is drawn into the story. Generally, many works depicted with such long shots depict the climax, and there are few works that draw the viewer into the story. Kunichika is able to depict the story in a way that makes the viewer recall the story when they look at it, as in this painting. However, many of Kunichika’s long shot paintings also suggest the entire play.

.

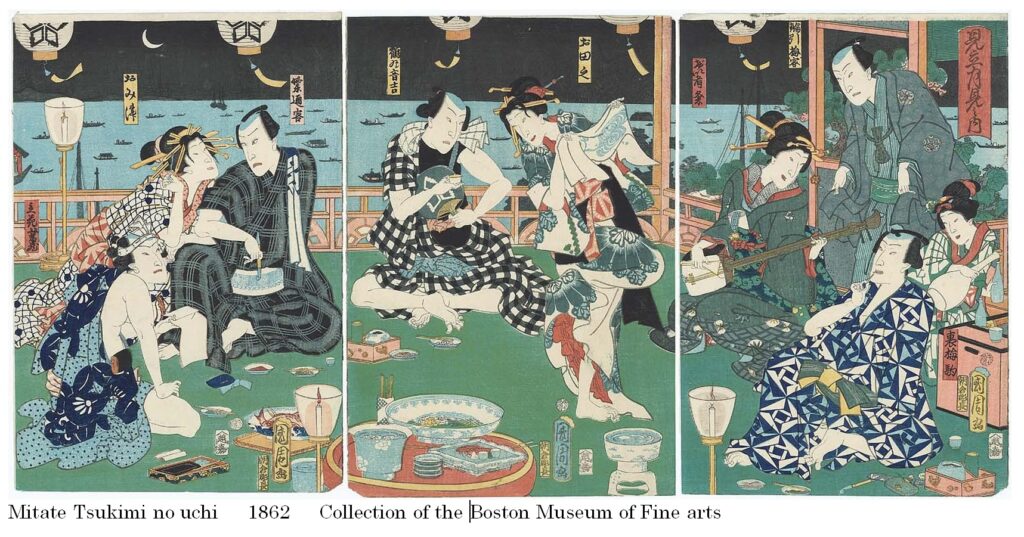

The next painting is “Genji no waka Ohmihakkei “, a work from 1863. Genji is enjoying sake and snacks by a quiet river on a moonlit night, and the atmosphere seems to become lively as the princess recites a poem or dances. It is drawn in a long shot, so the facial expressions of the people can be read, but the viewer can also look at it objectively and contemplate the atmosphere depicted.

.

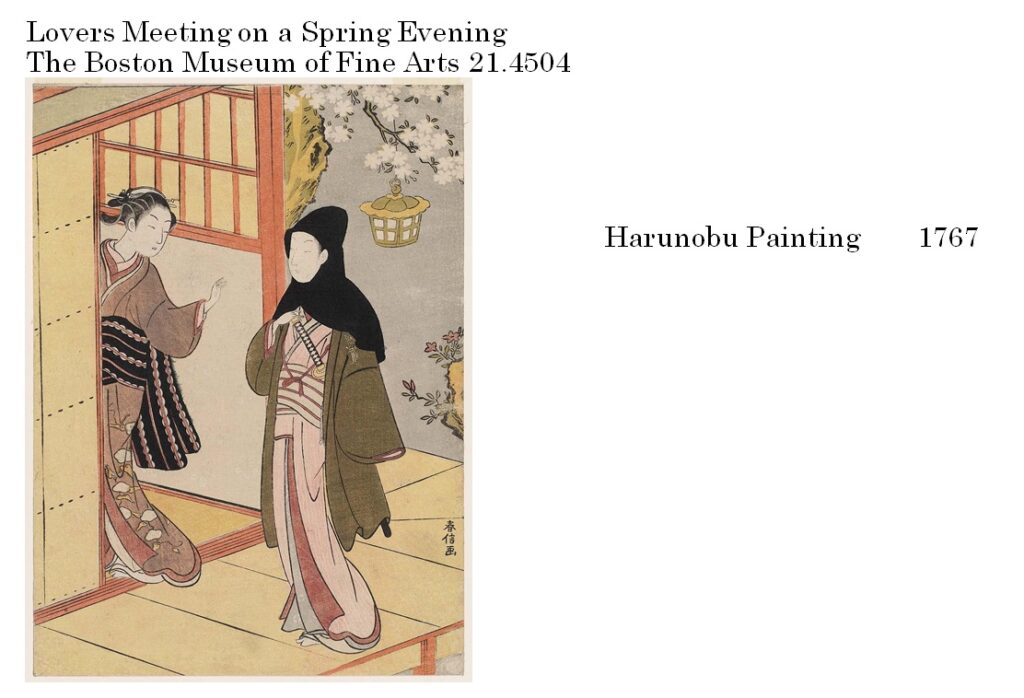

Here are some similar long shots with the whole body drawn. Suzuki Harunobu’s standing ukiyo-e “Lovers Meeting on a Spring Evening” has a background, while Harunobu’s “Yoshiwara Bijinai” and Kiyonaga’s “Minami eki no kei” do not. “Lovers Meeting on a Spring Evening” has two people drawn, and the whole body is drawn in a flowing style of kimono influenced by Chinese paintings, giving the impression of a relaxed movement. One is a man wearing a hood and carrying a sword. The other seems to be guiding, or talking to the hooded person passing by. It is reminiscent of spring with cherry blossoms in bloom, and the lanterns suggest that evening is approaching. A beautiful woman is depicted in this setting, but the woodblock print is packed with other information as well, making it an ukiyo-e with enough information that it could be used to tell a story. The painting shows the two people standing and their relationship objectively, and their thoughts and expressions are not clearly expressed. In this way, the picture conveys a place and atmosphere.

On the other hand, “Yoshiwara Bijinai” and “Minami eki no kei” with the background omitted show the beauty itself. The plain background and the soft, flowing kimono with the whole body standing allows the viewer to concentrate on the picture of the beauty itself. The movements are also gentle and not violent. This allows the viewer to focus on the beautiful woman standing and her attractive face. The composition of the standing figure is viewed objectively by the viewer, but the inner thoughts of the woman are not expressed.

The paintings by Suzuki Harunobu and Kiyonaga introduced here are so-called “bijinga”. The women are drawn slender and tall, with a willow waist, narrow eyes and a mouth narrower than the eyes, depicting the beauty of their standing figure and the beauty of their face. In this long shot, the facial expression is drawn deadpan, making it easier for the viewer to get attached to them, and giving the impression that they are looking at them from a distance. It seems that many Japanese researchers think that if a woman is depicted in an ukiyo-e, it is a bijinga. The theme of a bijinga must be female beauty. Interestingly, there is no word overseas that corresponds to the genre of “bijinga.” Regarding this issue, Hiroshi Deguchi (28) argues that bijinga has a sensibility similar to today’s “moe,” but different from shunga.

.

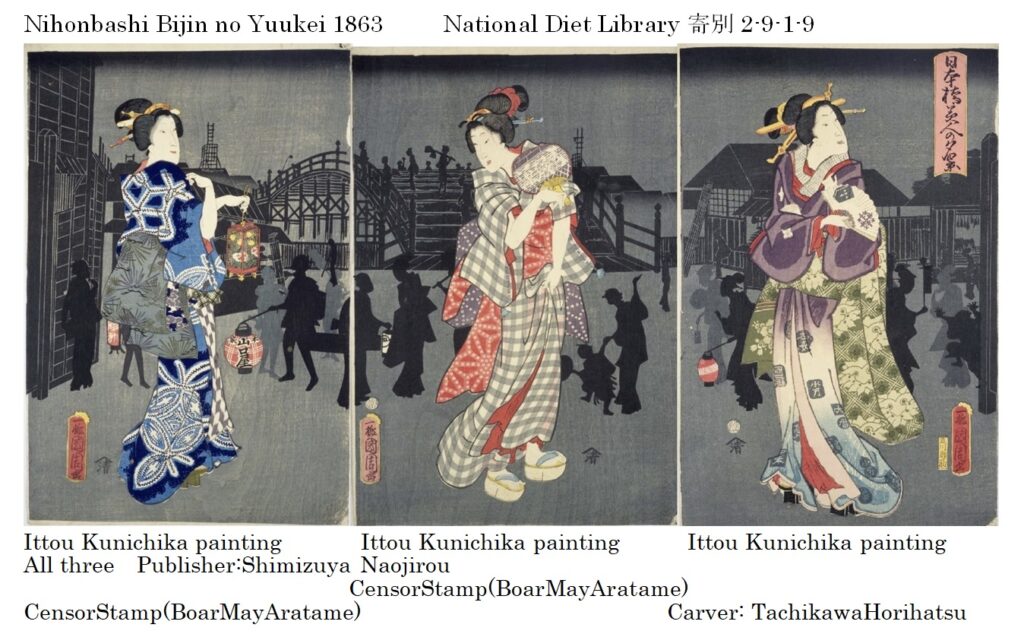

In the following “Nihonbashi Bijin no Yukei”, the liveliness of Edo Nihonbashi is expressed in black and white. As a result, the standing figure of the woman in the foreground stands out. Kunichika makes the patterns of the women’s kimonos flashy to match the background, but in this painting both the colors and patterns are elegantly put together. The style of drawing draws attention to the standing posture and facial features of women. The silhouettes in the background are not only black, but also grey, which gives the overall image a sense of perspective; this is a wonderful way of drawing. The woman in the center is wearing her wooden sandals and has her hem tucked up, and she looks like an innocent girl. Unlike Harunobu and Utamaro’s paintings of beautiful women, this is a familiar painting of beautiful women with a downtown atmosphere.

.

As described above, since the composition is drawn as if it were seen from a distance, the background and stage are drawn, and the background of the story can be understood. The characters are depicted in a full-body standing posture, and it is possible to understand who is conversing with whom by the facial expressions of the depicted characters, and a little what the characters are pondering. In this way, an objectively drawn long-shot picture is a picture that understands the story. In the case of bijinga, it is a picture that admires the figure and face, and is a picture that is viewed objectively.

3-6B) Medium shot, case of 1 person/paper

A medium shot is introduced, in which a single beautiful woman or actor is depicted from the waist up, including the arms, on a large piece of paper. In this case, the stage and other background are omitted, so the actor’s personality, movements, and the atmosphere of the scene are shown, emphasizing the character’s movements and expressions. Kunichika’s numerous actor paintings are an example of this.

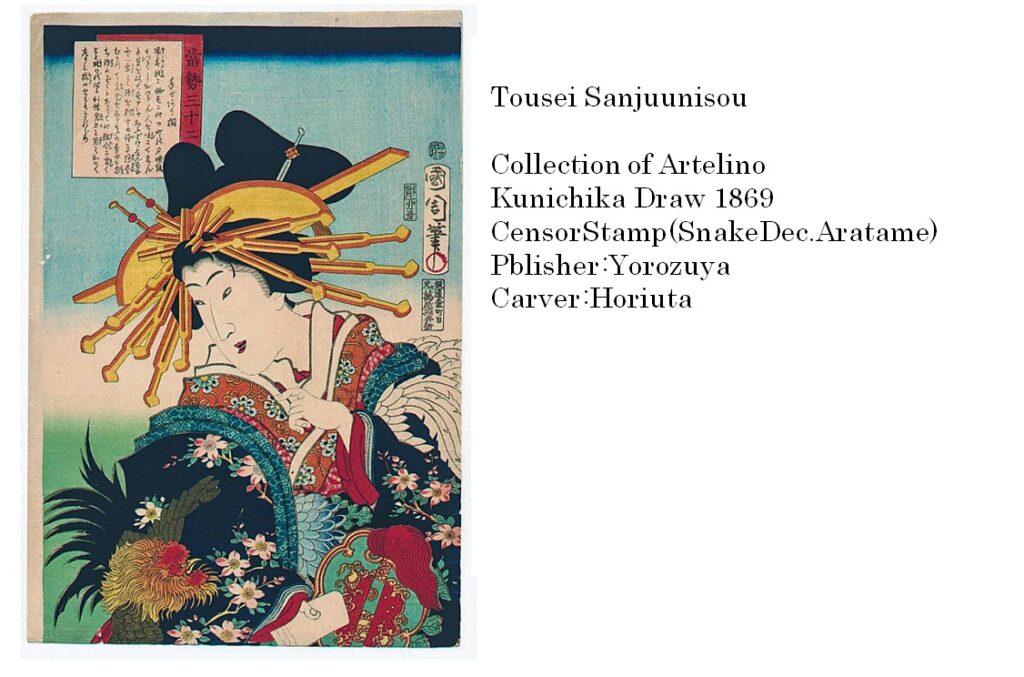

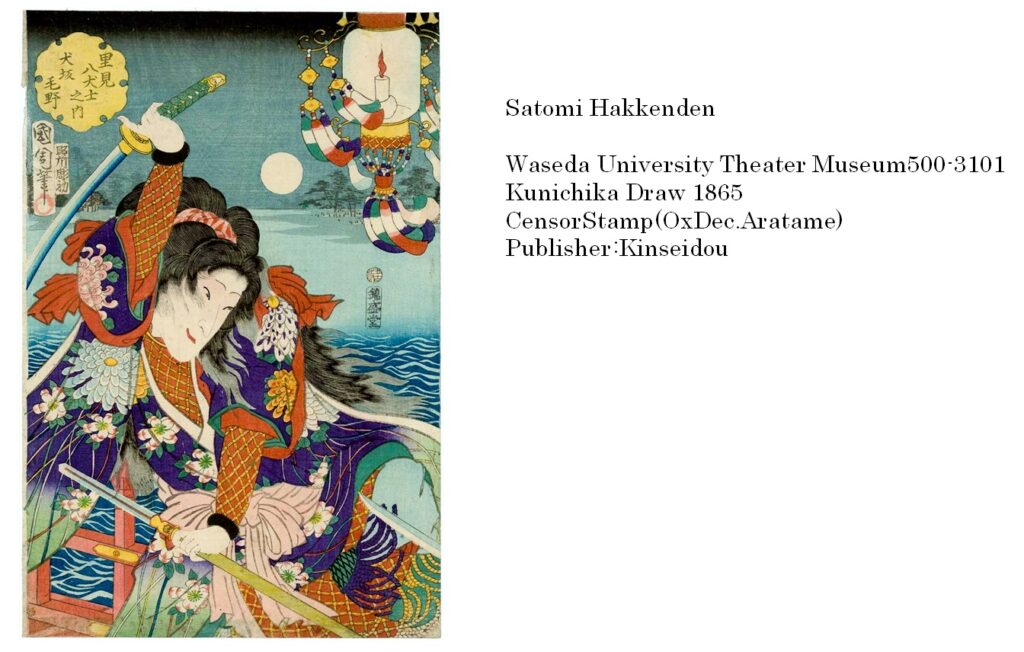

As examples, “Touto 36kei no uchi Atagoyama” and “Satomi Hakkenshi” are introduced. As the background is also depicted, the viewer is objectively and smoothly drawn into the world of the play, with the intense movements of the moment and the actor’s situation and what he is trying to do, and the story can be read from the actor’s expressions. It gives the impression of a scene from a kabuki play, or a scene from a story. The movements of the depicted figures reveal intense movements and emotions. It is different from a long shot in that the character’s expressions are visible, so the viewer can concentrate on the character’s personality and feelings depicted from the character’s actions and expressions.

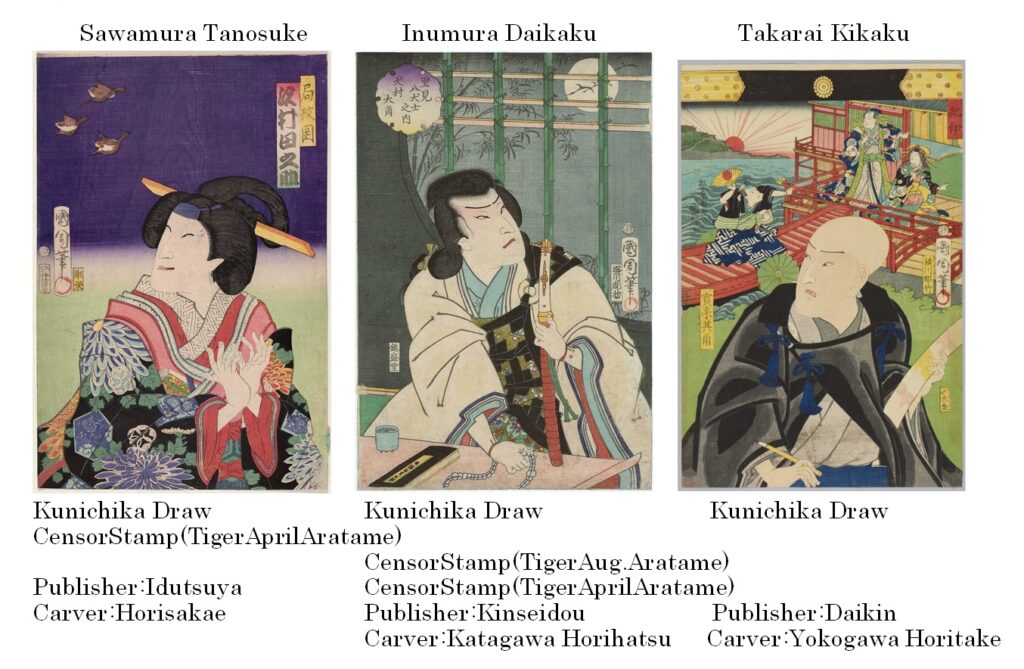

Three medium-shot pictures are introduced. The background is drawn differently. The painting of Sawamura Tanosuke has no background, so the viewer is left wondering what she is thinking. In the painting of Inumura Daikaku, the moon and geese are depicted in the background, depicting Inumura mulling over various things and coming to a decision after dark. The picture of Horai Kikaku on the far right is a method of explaining situations that are not related to time or physical distance of the main character, such as Horai being the main character but the background being memories. In this way, Kunichika expresses the feelings of the protagonist.

.

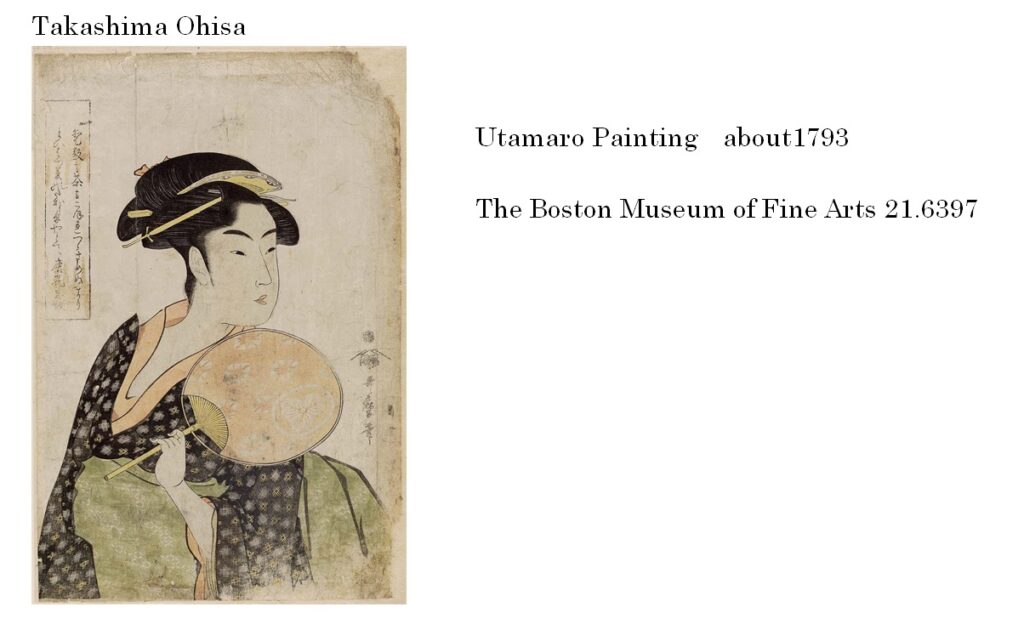

Medium shot compositions create pictures that evoke emotion, and Kunichika began to paint many of them. Furthermore, by using a medium shot with little background, the subject’s inner thoughts and emotions become the main theme. It becomes a portrait, and also a Bijinga. As there is no other information available other than the person, the viewer will naturally focus on the person. The viewer’s gaze is drawn to the person’s movements and facial features, and so it comes into existence as a Bijinga. This is Utamaro’s Takashima Ohisa.

.

The exhibition features Kunichika’s cute portraits of beautiful women, similar to modern manga. Kunichika generally paints kimono patterns with flashy designs, as in the courtesan he painted in “Shigeoka”(Chapter2, 1860), which draws the viewer’s attention. As a result, attention is not drawn to the appearance of the women, and it is said that Kunichika is poor at painting portraits of beautiful women. However, in these three works, it is the faces and expressions that draw the viewer in. Inusaka Keno is brandishing a sword, but her movement appears to be frozen. In all cases, the background information is limited, and the eye is guided to the women’s faces. This is the defining feature of a medium shot.

.

The next picture in the medium shot painting depicts Kawarazaki Gonjuro and Sawamura Tanosuke as kind and cute characters. The surroundings are not depicted, and the two are gazing at each other in silence. Anyone familiar with the play will recall a specific scene and be able to empathize with the scene. The fact that there are more medium shot paintings like this means that Kabuki is popular and more people can understand the content of the painting without the need for a long shot to explain the play. Around 1863, Sawamura Tanosuke and Nakamura Shikan were two of the most popular actors. Tanosuke was popular for playing weak female roles. Such a gentle image is depicted. This painting gives the impression that something is about to begin, and does not depict a scene where the characters show off at the climax of a Kabuki play. The development of the story is left to the

viewer.

.

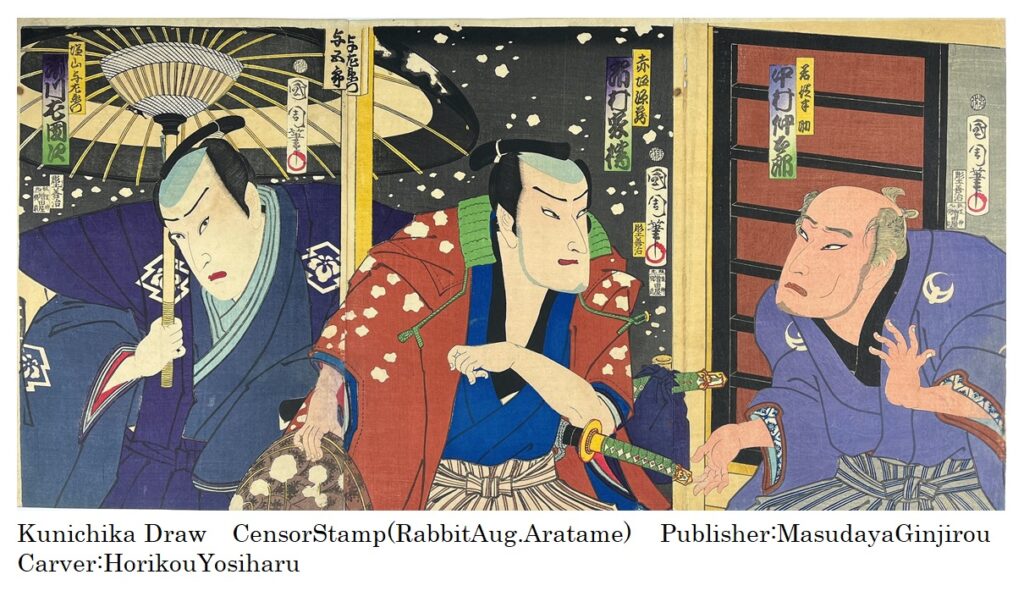

Akagaki Genzo (center) came triumphantly in the snow while Wakato Hansuke (right) was bewildered. Shioyama Yozaemon (left) is listening behind Akagaki Genzo in the next picture. This is one of Chushingura’s side stories, Shioyama is the older brother and Akagaki is the younger brother. Younger brother Akagaki will carry out the raid tomorrow, so if it ends, he will be sentenced to death. Akagaki visited with the intention of sharing a drink with his brother Shioyama for the last time in his life. However, Akagaki pretended to be drunk and playful so that his raid plans would not be known, therefore he was thought to be just a drunkard and hated. In this painting, Akagaki comes to visit and informs his manservant of his visit. His older brother, Shioyama pretends not to be home, but is curious about Akagaki’s visit and listens in intently. Kunichika is skilled at expressing facial expressions, so he draws his characters in such a way that the story can be understood just from their facial expressions.

.

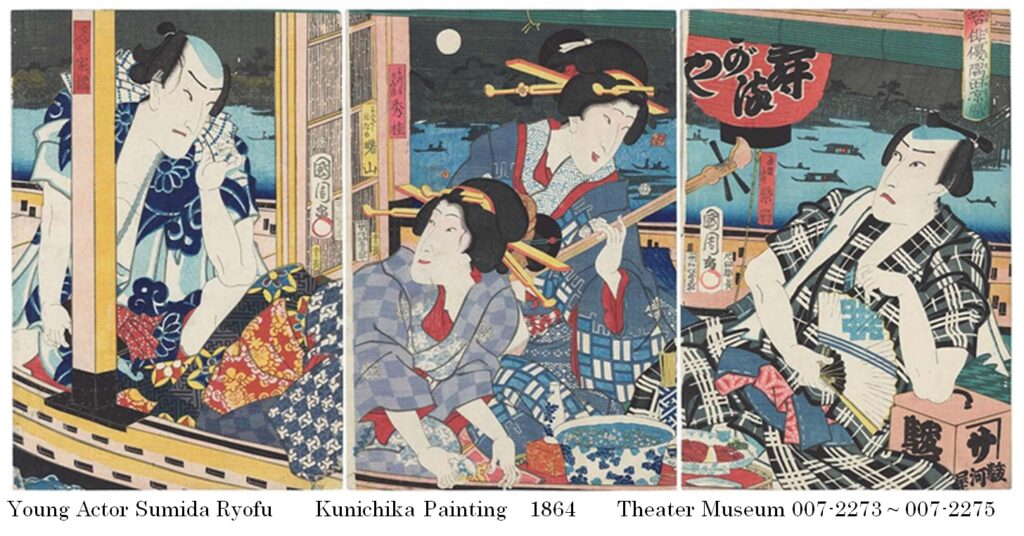

“Young Actor Sumida Ryofu” (1864) is a close-up approach to the characters, without explaining exactly where they are playing, but by expressing their facial expressions vividly, emphasizing the feeling of “enjoyment” to the viewer. The method of showing the painting lures the viewer into this place of entertainment. It is understood that the sense of familiarity is different compared to “Genji no waka Ohmihakkei” (1863) introduced earlier. When the characters are drawn in medium shots like this, the emotions of the characters and the power of the painting are combined to create a powerful picture.

.

As described above, the surrounding situations are omitted, but the expressions of the characters are depicted richly, so one scene of the story can be understood. In addition, the viewer is drawn into the depicted scene. The feelings of the characters drawn in the way the background is drawn are also emphasized. In the case of paintings of beautiful women, there is a sense of intimacy that comes close to the inside of the person depicted.

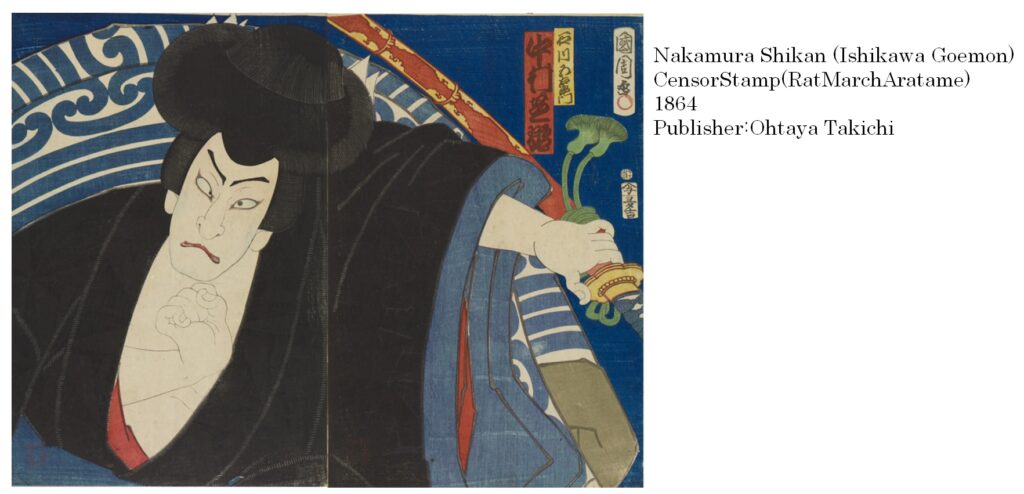

3-6C) Medium shot 1 person / Two large papers

Compared to the case (3-6B Medium shot, case of 1 person/paper), the aspect ratio of a single person in a medium shot on a large double sheet gives the viewer a completely different impression due to the relationship with the left and right margins. Kunichika has created several powerful works of a single actor on double sheets, but the work introduced here is thought to be his oldest one-person/two sheets. The composition is like modern art. The sword grasped in the left hand is in motion, and the right hand is removed from the chest, as if about to draw the sword, creating an overall dynamic picture. Nakamura Shikan’s Ishikawa Goemon is a large double sheet from 1864, drawn in a medium shot across the entire page. It depicts a spirited shout and a powerful scene of the actor rushing out with his sword in hand, about to take off his clothes. This composition can also be used in modern posters. The aspect ratio of the large-format piece is different from that of these two pieces. In other words, the width from top to bottom is longer than the width from left to right. Therefore, when the picture is drawn, the left and right sides become narrower, eliminating the wasted space. This eliminates waste on the screen and makes it more powerful.

.

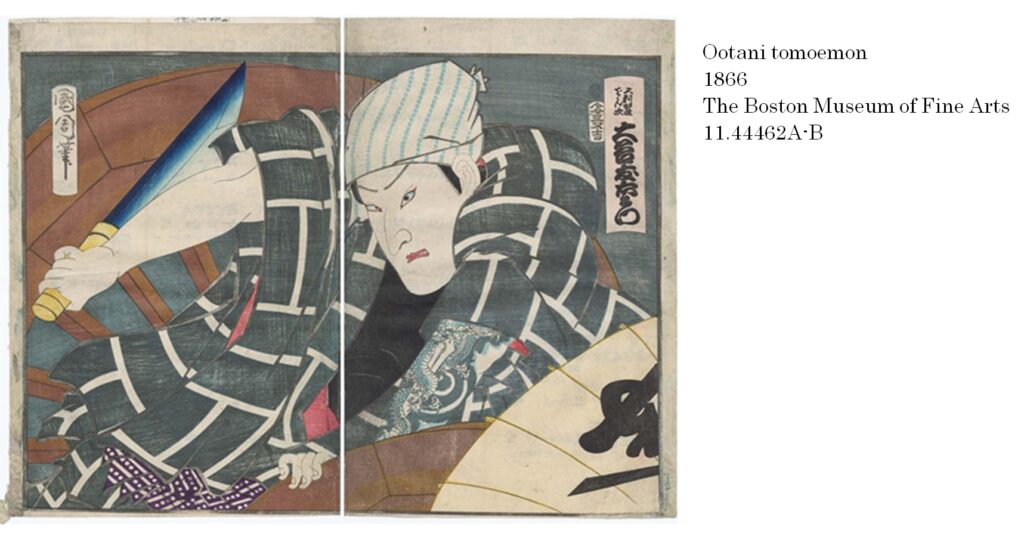

There is a work “Ootani Tomoemon” (1866) depicting actors in two large papers. In this case too, the aspect ratio is 1:1.33, and there is almost no background. The little information depicted is that of the wheels of a large cart, but the image of Ootani Tomoemon glaring and brandishing a long knife is powerful. This painting, twice the normal size, was likely evaluated as a very powerful painting.

.

As mentioned above, with a medium shot of one person/two shots composition, there is no wasted space around the subject, so the viewer feels as if they are right next to the subject, and it also creates the impression that the viewer and the subject are about to bump into each other. This method of drawing is similar to Ohkubi-e, but by drawing on two large papers, it is possible to explain the situation, and it expresses even more violent movement.

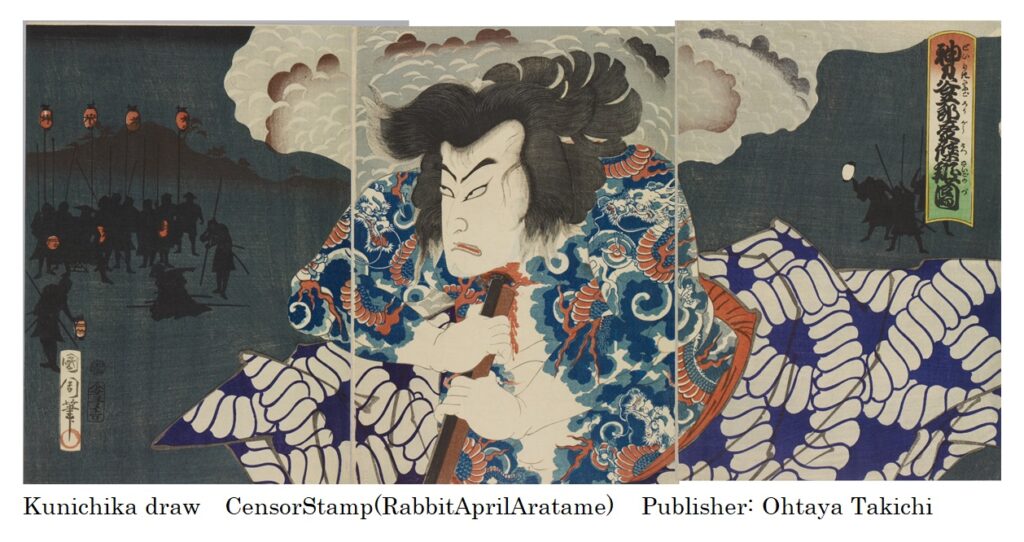

3-6D) Medium shot 1 person / Triptych

Next, consider the meaning of drawing one actor on triptych. Kunichika draws many works on Triptych, but when it comes to drawing one person on triptych, this is an extreme panoramic screen with an aspect ratio of 1: 2. The aspect ratio of HDTV is 16: 9, which is longer than this, but shorter than 1: 2.35 of the cinemascope. In the world of painting, such a horizontally long screen is suitable for landscape paintings that enjoy the blank space. The background of this screen is too long for the actor alone, and the margin is too large to express the actor’s movements and emotions. However, Kunichika drew a picture that overcomes the drawback that the surrounding space dilutes the spirit of the actor.

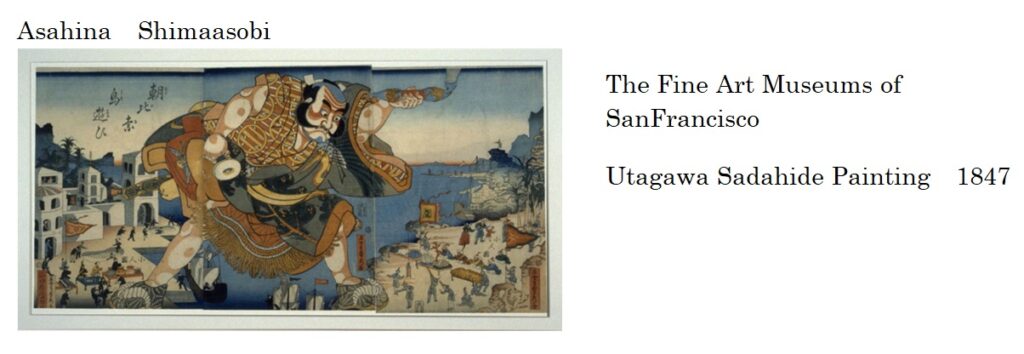

As an ukiyo-e depicting one hero in Triptych, there is “Asahina Kobito Shimaasobi(朝比奈小人嶋遊)” drawn by Kuniyoshi in 1847. The painting depicts Asahina lying down and happily watching a small daimyo procession like an ant walking in front of him. There is also “Asahina Shimaasobi(朝比奈島遊び)” released by Utagawa Sadahide in 1860. In each case, the panoramic screen is used to draw a dwarf around the big hero, and one hero is placed large, so there is no waste in the composition. The country of dwarfs cannot be drawn sufficiently with the two large papers set. However, these paintings express “interesting scenes” and appeal to the viewers of the paintings, or they are only visually interesting, and nothing more. Furthermore, these paintings were drawn in long shots, but Kunichika drew them in medium shots, which is even more difficult.

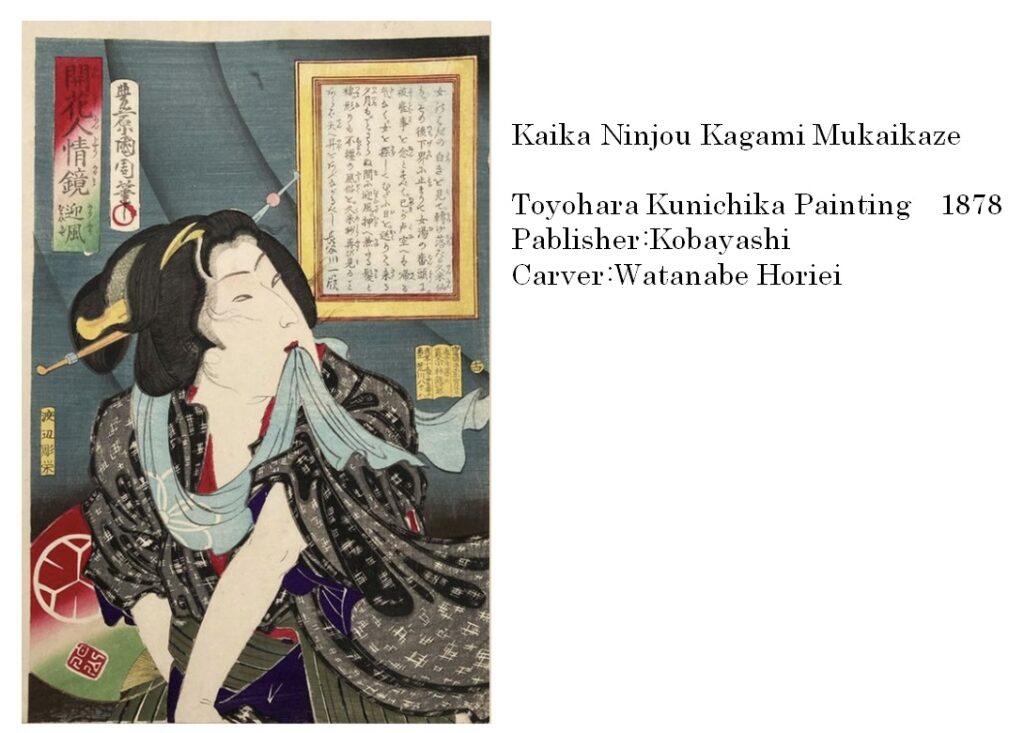

Kunichika’s first work depicting a single actor in a medium shot on a large-format triptych drawn with this composition is “Jinriki Tanigorou Gouketsu Saigo no zu.” It expresses the regret that Tanigorou feels as he commits suicide in despair. The light of his pursuers is faintly depicted in the dark background, explaining how he was chased by the enemy. If the theme is brutal suicide, the one in the center is sufficient. If Tanigorou’s whole body was depicted, the story would be viewed objectively. However, this painting is a medium shot, and the wide space around it emphasizes the feeling of loneliness, which amplifies the feelings of despair and regret expressed in the painting.

.

.

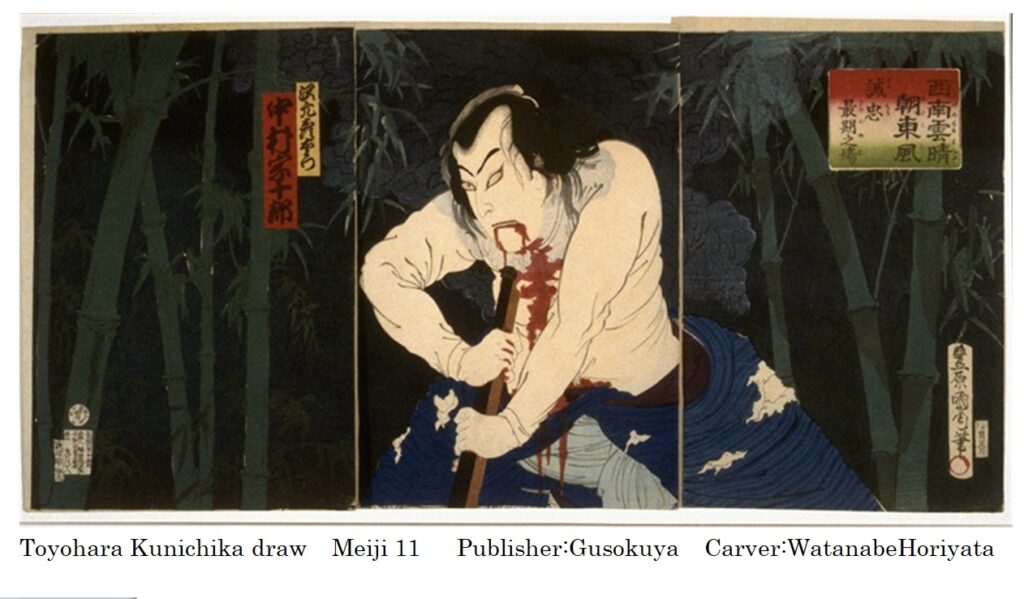

This is similar to “Jinriki Tanigorou Gouketsu Saigo no zu” but also to this 1878 “Okigenokumo Haruasagochi西南雲晴朝東風誠忠最期之場” which is also a painting of suicide. The dark background shows a gloomy atmosphere, a state of loneliness and despair. Furthermore, there is no explanation of the pursuer like the previous work. Therefore, death is the theme, and it is a picture of self-harm in various thoughts leading to self-harm. As a result, it has a stronger impression as an expression of the main character’s feelings. The picture in the center could be completed by itself, but if that were the case, it would be a picture that expresses the magnificence of self-harm itself, and no further story emerges. There is a necessity to make triptych here.ff

.

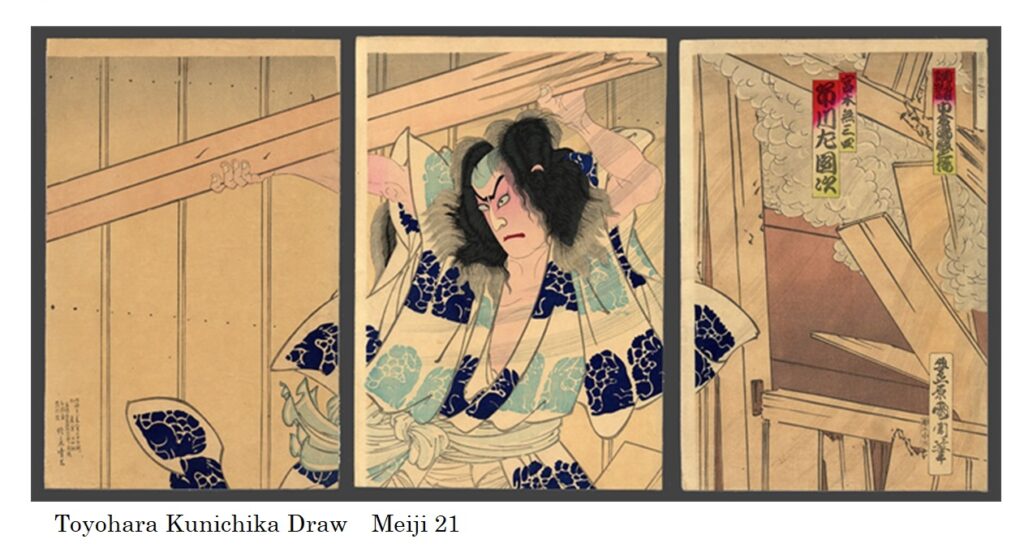

In the 1888 painting Ichikawa Sadanji, Musashi is rampaging across the screen. By using a panorama screen and a close-up of the person, his angry emotions can be appealed to the viewer of the ukiyo-e. In this case, the more the character is drawn smaller and the surroundings are drawn, the less the actor’s anger is expressed. If so, the picture will simply be a picture explaining the rampage. Kunichika used medium shots to express the emotions of the characters, and added meaning to the blank space to amplify the emotions of the characters. It’s a wonderful way of conveying the feelings of the characters to the viewer.

.

An earlier triptych painting of an actor similar to this style was simply a “funny scene” piece. Kunichika’s medium-shot drawing of one actor in a triptych produced a completely different effect. It is the effect of using the surrounding space to amplify the emotions of the characters. It is believed that Kunichika created this composition not only by depicting the actions of the characters, but also by expressing their feelings. Regarding this style, Yoshida Eiji described this style as follows. “The way he draws the half body of one actor in a triptych is a work that uses a large screen extravagantly, and is his innovation.” (29) He evaluates it as a notable style.

3-6E) Ohkubi-e (close-up)

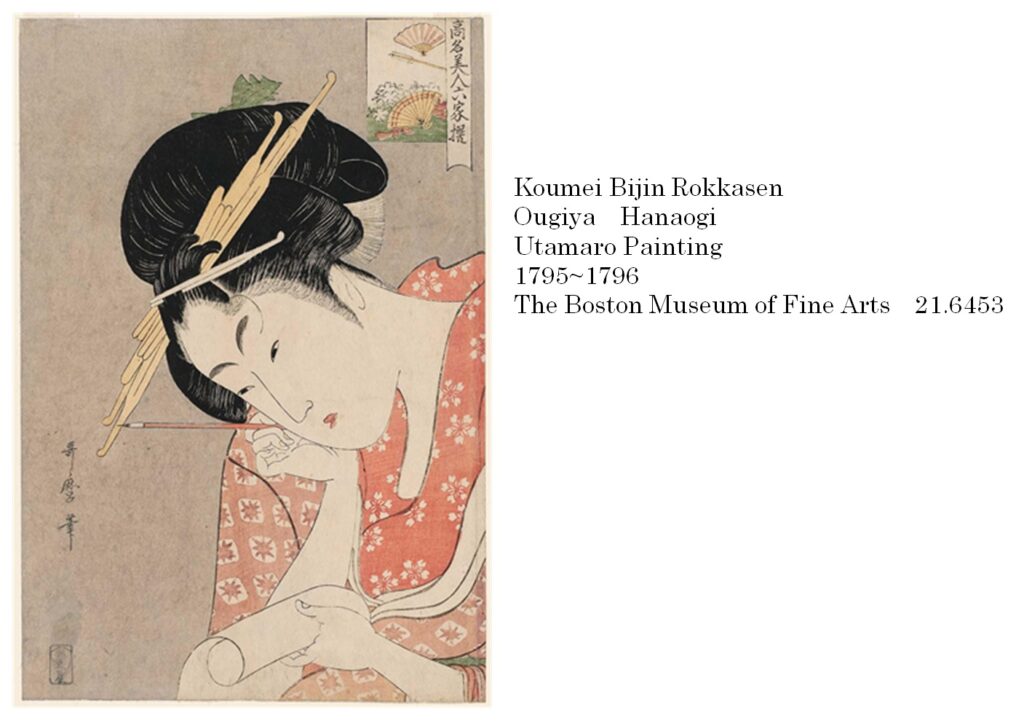

Close-ups are done from the chest up, and although the arms are often not included, they are drawn up to the wrists. This is a style of painting that gives the impression of seeing a beautiful woman up close, rather than viewing the whole figure from afar in ukiyo-e. This style of painting allows the viewer to exchange voices with the beautiful woman and empathize with her actions. Traditional standing portraits of beautiful women are viewed objectively, but close-ups create a completely different feeling for the viewer. This is called Ohkubi-e. Ukiyo-e known as Ohkubi-e are famous for being painted by Sharaku and Utamaro, but in the past, Shunsho and Buncho painted them as pictures of folding fans. Shunko painted them as single pieces several years earlier than Sharaku (30, p95). However, Utamaro’s paintings are highly regarded as Ohkubi-e, which goes one step further. The women depicted in close-up by Utamaro are depicted as idealized beauties, and are titled “Koumei Bijin Rokkasen” to evoke specific people. Therefore, the faces of most of the works are the same.

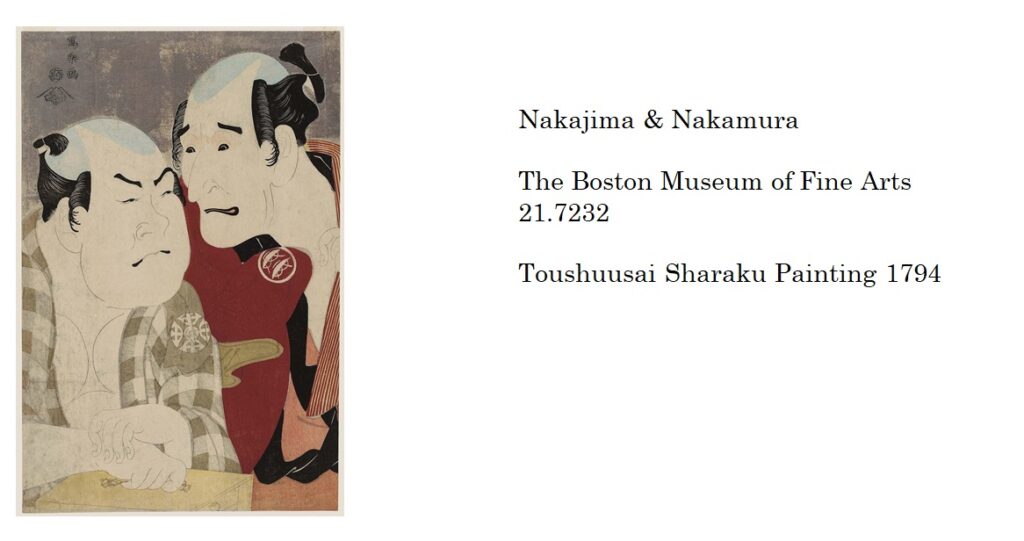

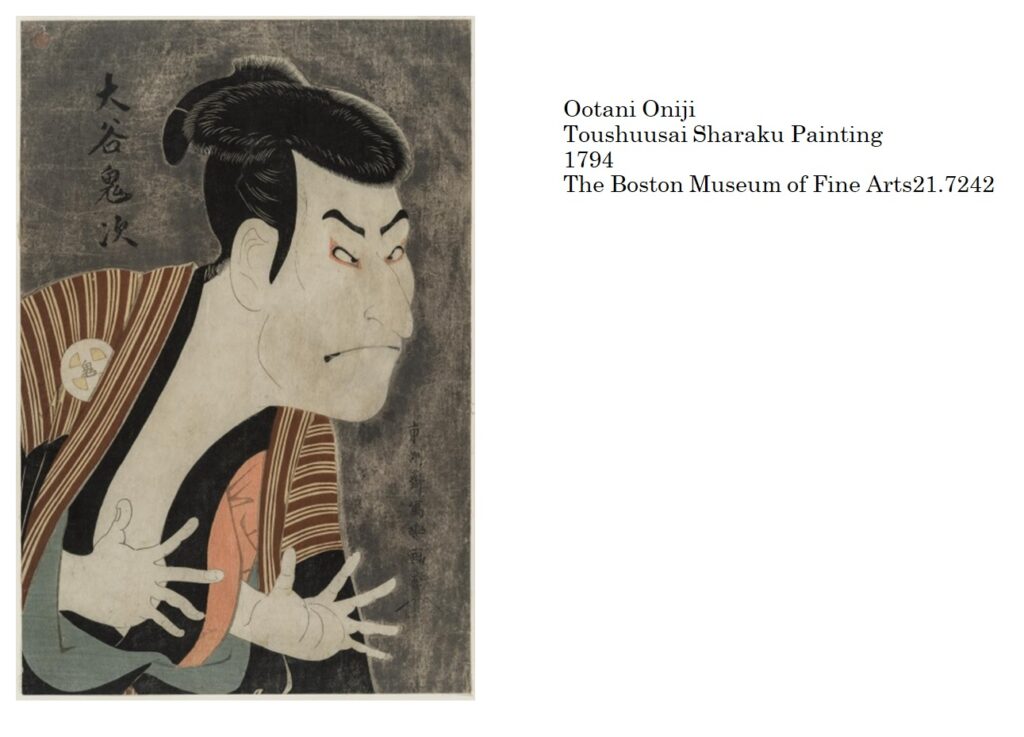

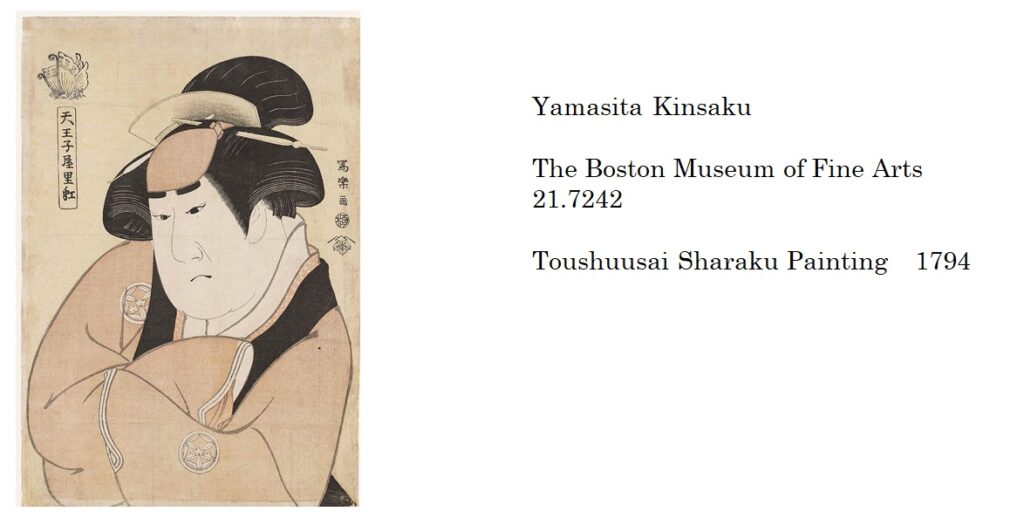

Toshusai Sharaku’s Ohkubi-e is in the same category as Utamaro’s close-up, and the novelty that still applies today is wonderful. All with plain backgrounds, they have perfected the so-called portrait photography type that would be taken in a photo studio today. In Sharaku’s Ohkubi-e, many of the pictures are simply labeled “Toshusai Sharaku,” and there are few works that list the actor’s name, such as “Nakamura Utaemon.” However, until then, there was little awareness of drawing different faces of actors. It is said that Sharaku sometimes exaggerated them, and went beyond the expectations of fans (61). Sharaku seems to have drawn portraits that are close to the real person. Since there is no information other than the character, the viewer is forced to focus only on the inner thoughts, feelings and moments of the depicted character. For those who appreciate this ukiyo-e print, information about hand movements is included, and combined with the facial expressions of the characters, it evokes various thoughts. It expresses the movement and personality of the actors themselves, bringing them closer to the viewer and giving them a sense of intimacy. In the three pictures shown here as reference, even in Sharaku’s Ohkubi-e, even if the viewer doesn’t know the story of the background, the expression and action show the story of this moment. “Nakajima and Nakamura” can be seen bewildered and pondering deeply, and “Ootani Oniji” can be seen approaching something. Sharaku paints many Ohkubi-e, but most of them are drawn with a glaring expression, except for the bewildered face in ‘Nakajima and Nakamura’ and the thoughtful face in ‘ Yamashita Kinsaku ‘. There are few works that reveal the inner thoughts and feelings of the characters like “Nakajima And Nakamura” and “Ootani Oniji” introduced here. It is reported that Sharaku’s Ohkubie was not popular because it was realistic as a portrait, unlike the ideal face that the actor played in the play(23).

.

As described above, Utamaro’s portraits of beautiful women create a sense of intimacy that makes the viewer want to snuggle up to the beautiful woman and talk to her. As a result, it becomes easier for the viewer to empathize with the depicted action. On the other hand, Sharaku’s Ohkubi-e depicts the inner thoughts and feelings of the person depicted, but they are not clearly depicted. For example, “Ootani Oniji” was established as a graphic painting that can be viewed objectively, and is now used in posters.

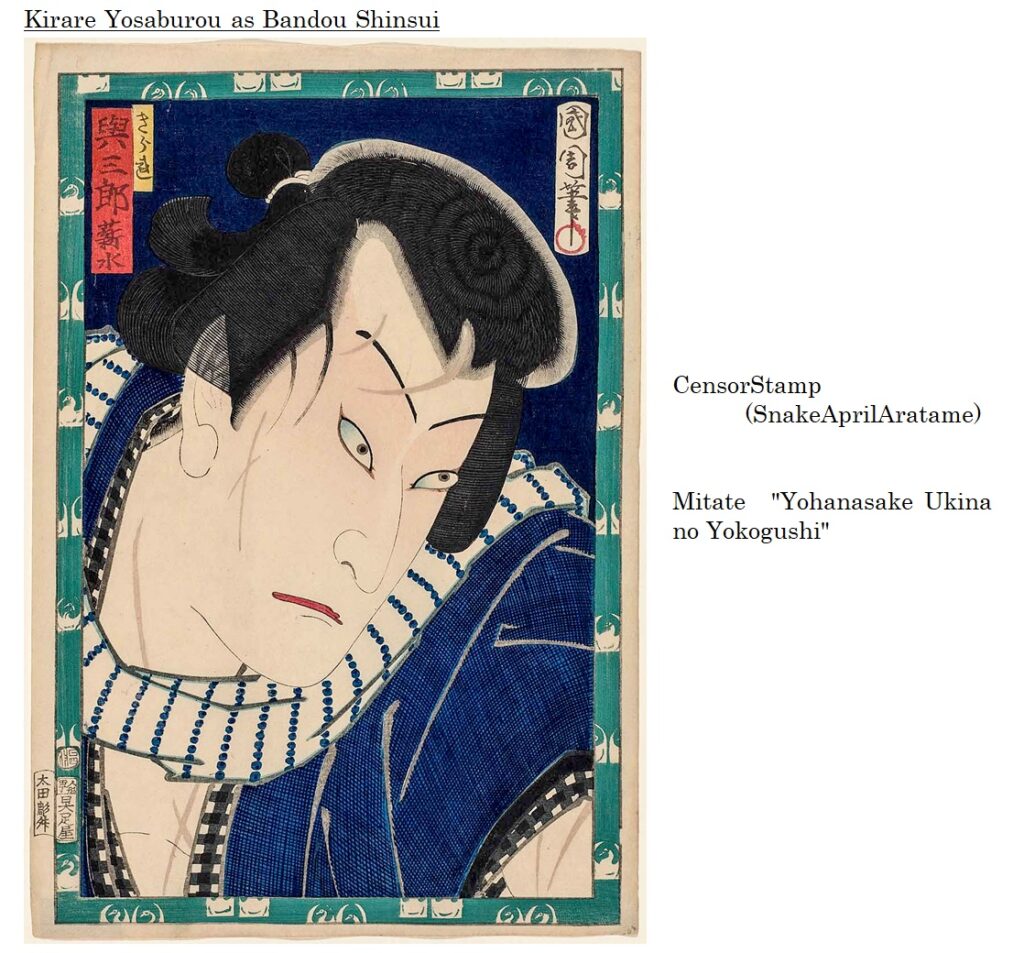

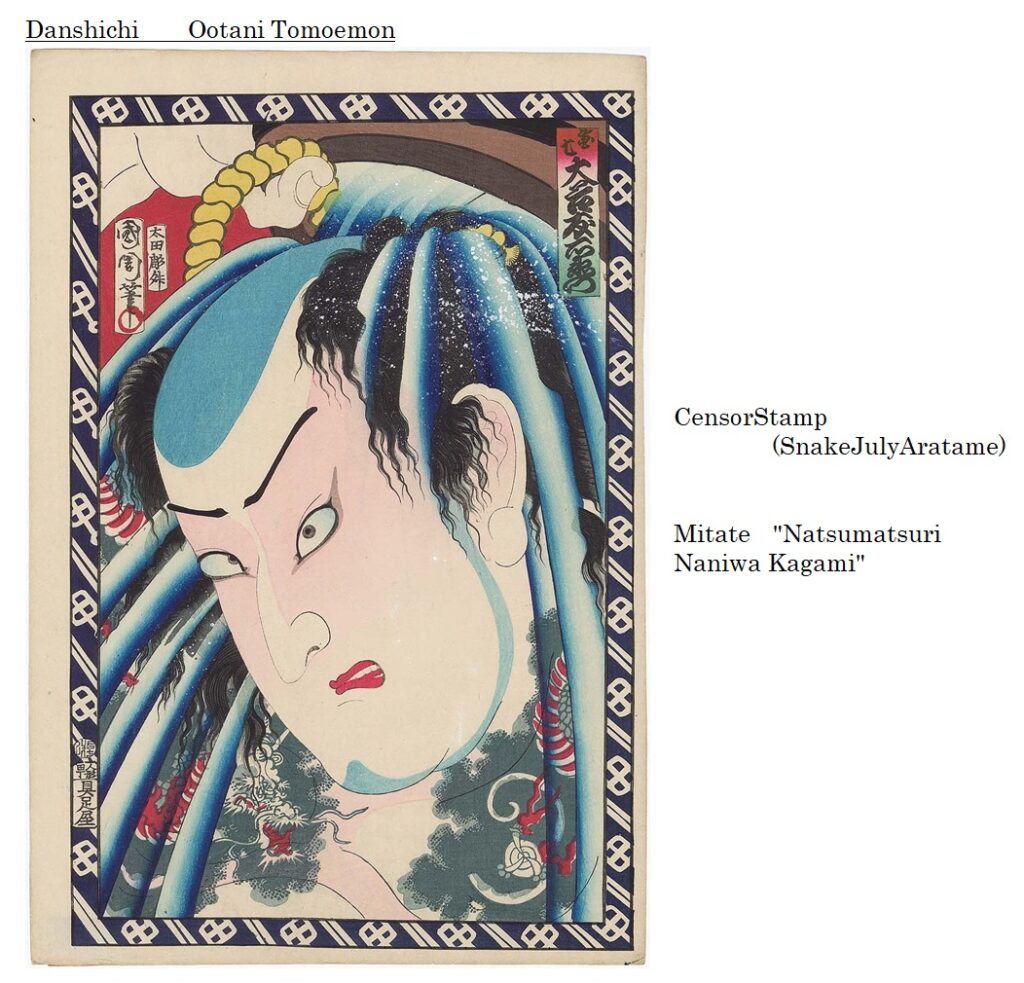

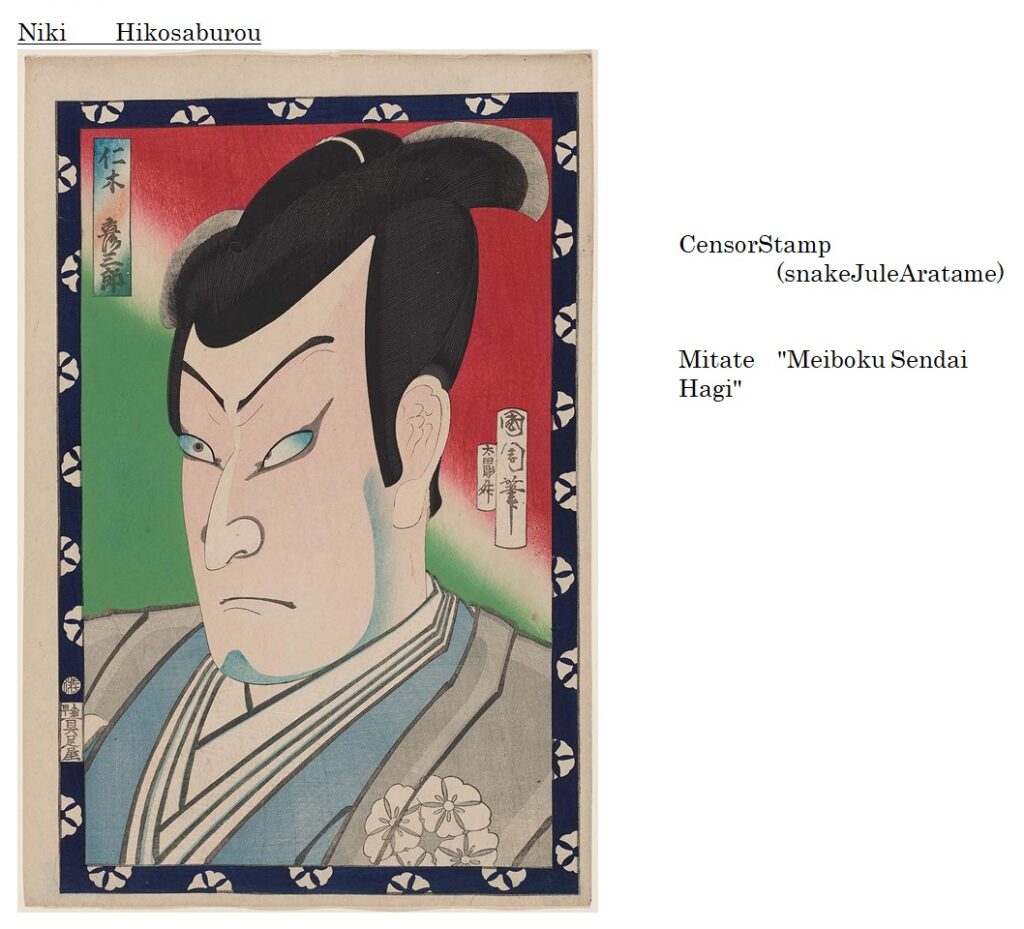

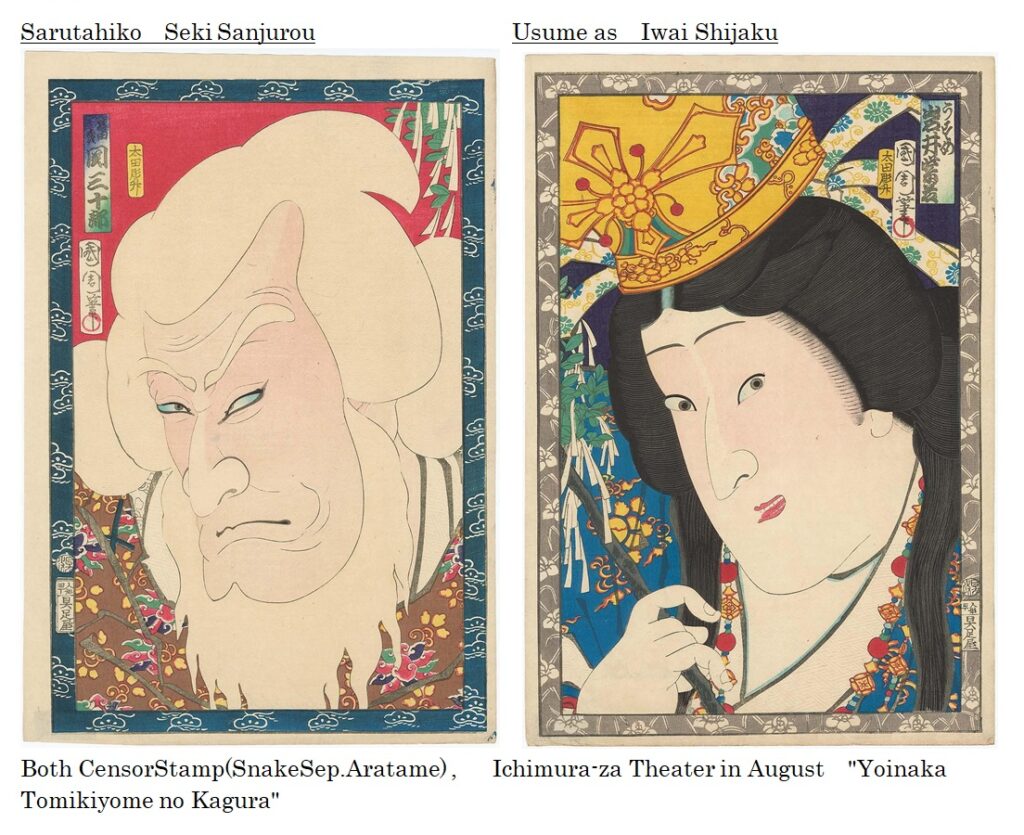

3-6F) Ohkao-e (Big close-up)

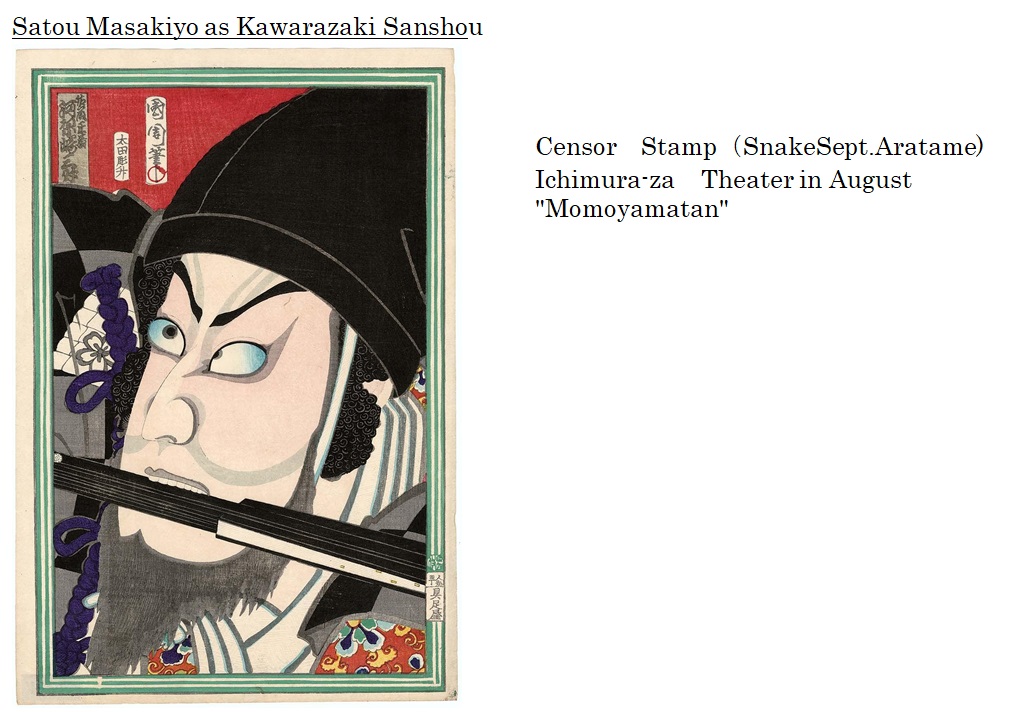

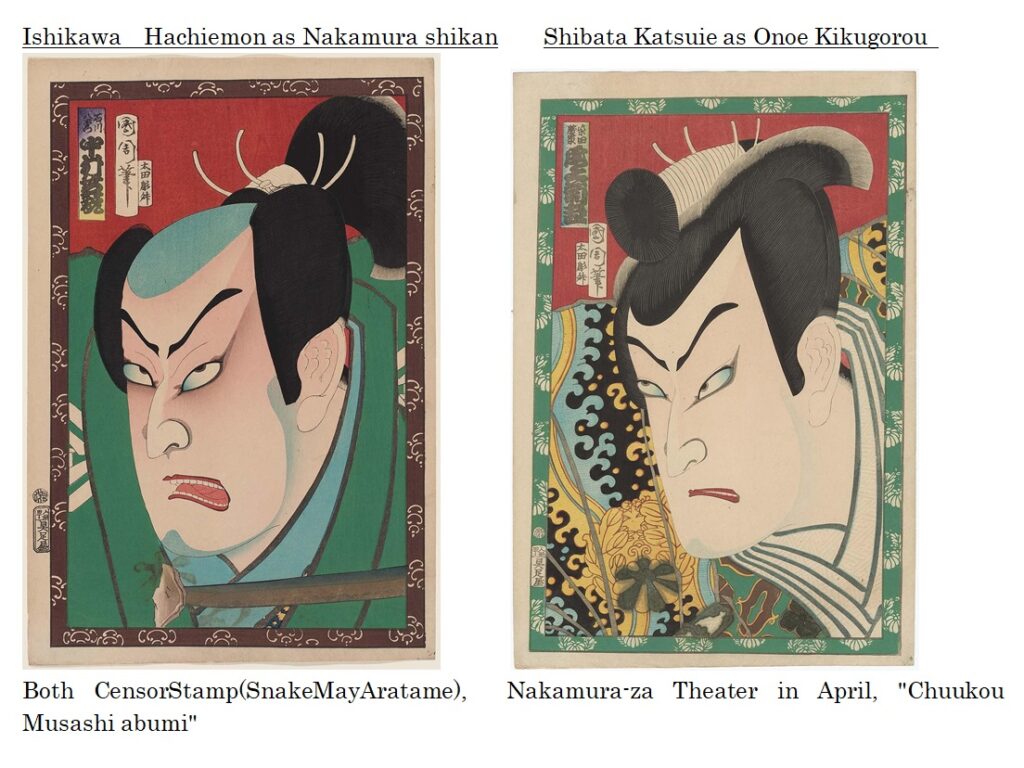

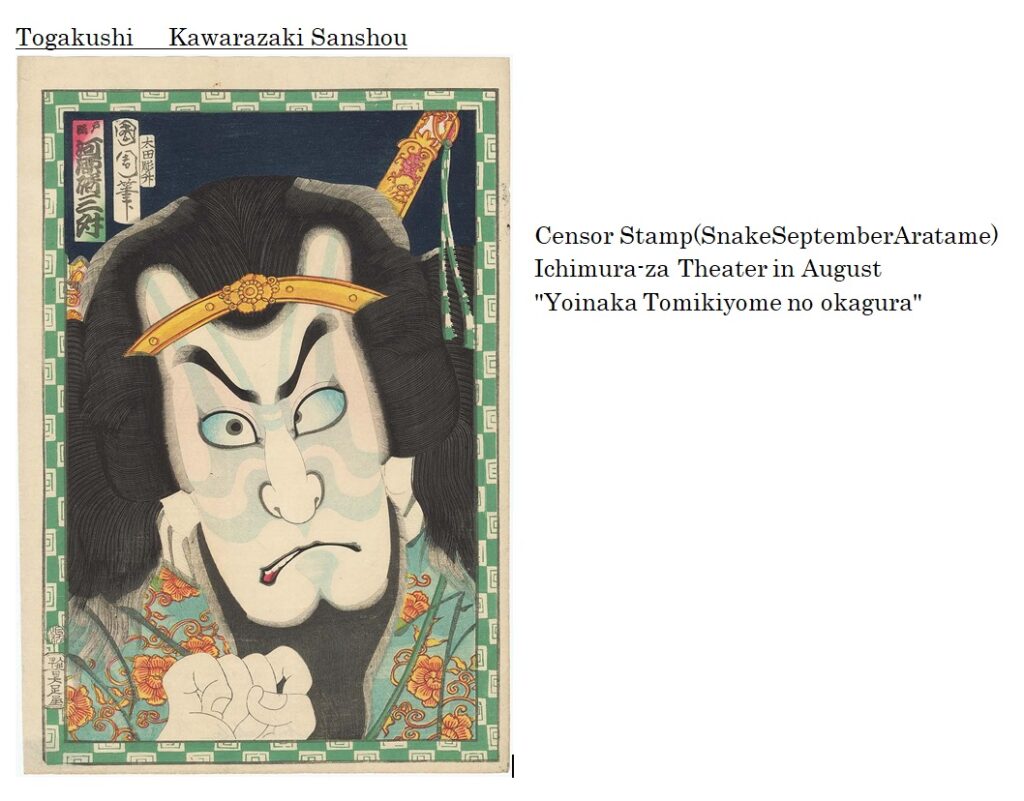

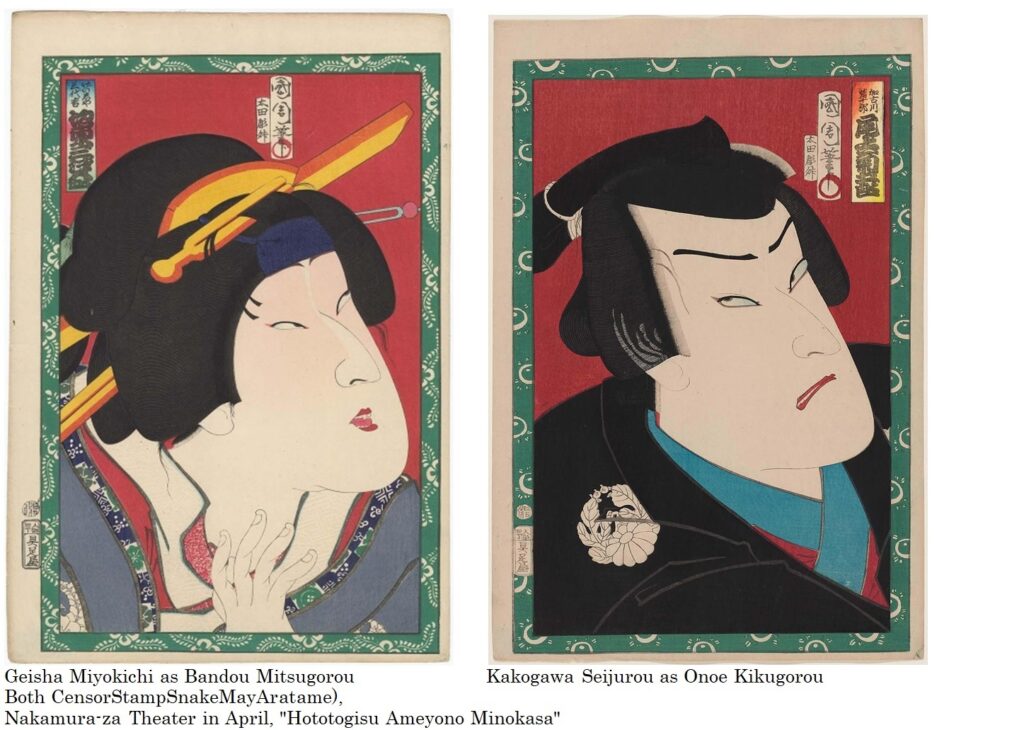

Ohkao-e (big close-up) is drawn from the neck up even closer than Ohkubi-e. In this way, the viewer can read the character’s feelings from the expression, and the painting communicates the emotions and feelings of the character to the viewer. Most of the sets introduced here are based on Kabuki plays from 1869, but Kojima (1) states that Kirare Yosaburou, Niki, and Danshichi were drawn in Mitate. The other plays were confirmed in Kabuki Nenpyo, Vol. 7 (12). The following are detailed descriptions, but all of them were drawn by Kunichika, published by Gusokuya, and carved by Ota Masukichi, so explanations will be omitted. Kunichika’s Ohkubi-e includes the names of the actors and the names of the roles in the play. As mentioned in “3-5 Establishment of Actor Face Drawings,” Kunichika seems to have based his drawings on the real images of the actors and created the faces of the actors that the common people of Edo imagined. He then depicted the emotional expressions of the actors who performed in the play. It is understood that Kunichika included the names of the actors and the characters they played in the play with the hope that this would be understood. Kunichika’s Ohkao-e is different from Utamaro’s, who depicted an ideal image of a woman, and also very different from Sharaku, who depicted the real images of actors.

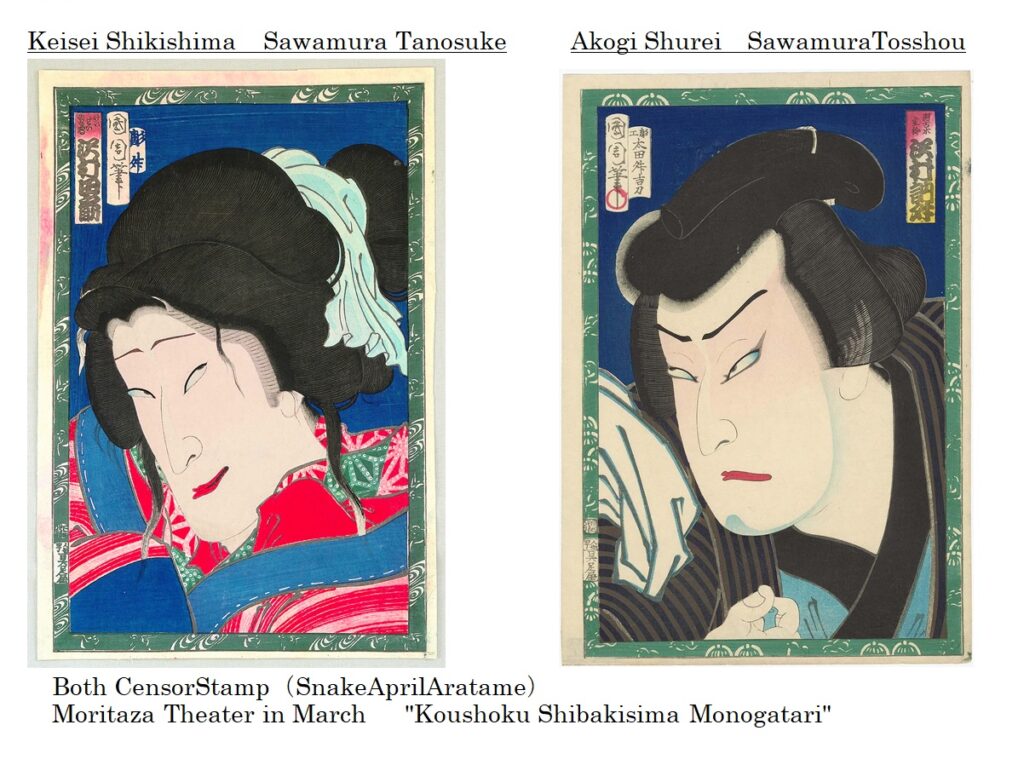

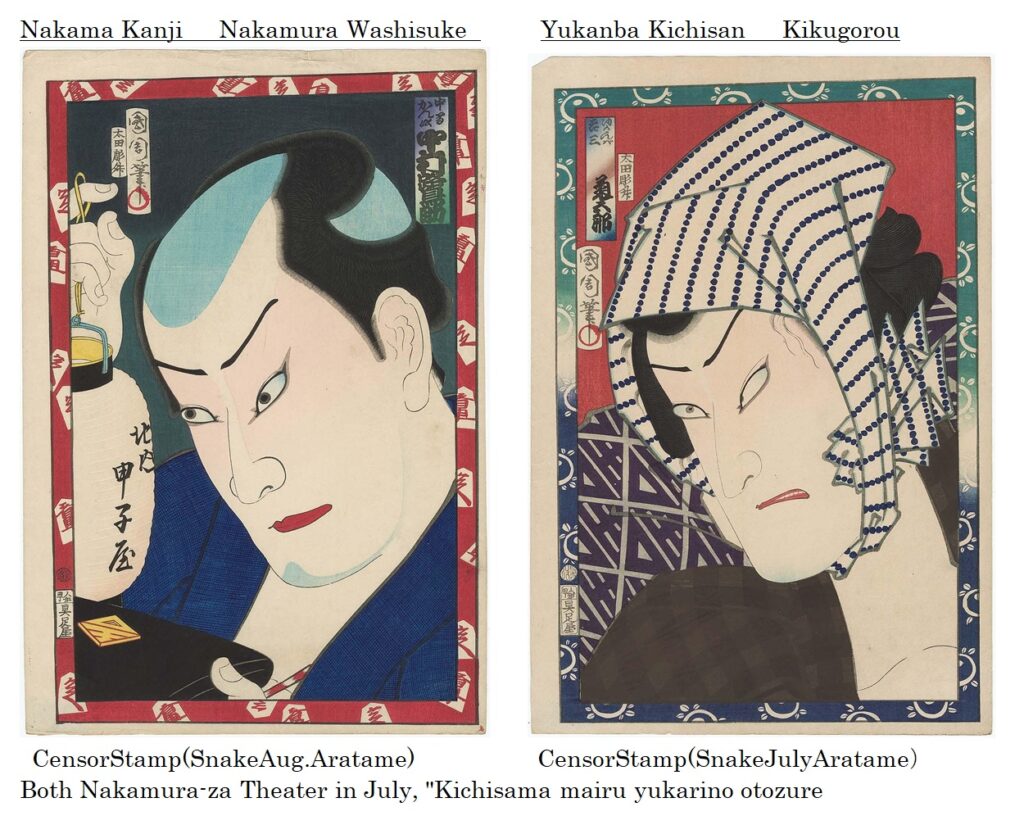

All works are from the collection of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

.

This “Keisei Shikishima” has a “suspicious” expression (a lie and a sense of incongruity, not wrong but somewhat suspicious). She lifted her eyebrows, her eyes were narrow and slanted, and her eyes were so high that her black eyes stuck to her upper eyelids. Her mouth is slightly open, and her neck is little tilted, just enough to catch a glimpse of her black teeth. With her suspicious look in her eyes, her cheeks are loose and contorted as if mocking her counterpart. The picture shows her with a sense of ease as she says, “You’re trying to deceive me with clever words.” According to the dictionary, the similar word “skepticism” is the feeling of doubting someone’s words and actions, and “suspicious” means to think something is strange, to feel suspicious, or to feel uncertain because it is not clear. This picture shows that suspicious expression.

“Keisei Shikishima” is a role performed in March 1869 at the Morita Theater, in the play “Koushoku Shibakishima Monogatari” (35,P159). Yoshiwara’s prostitute Shikishima is suspected of stealing money from her customers, and she is attacked and killed by Genshiro and Tsume. In fact, Otama, the proprietress, had instructed her husband Genshiro and prostitute Tsume. Later, Shikishima becomes a ghost. In the second half, Aoki Shurei, who had seen Otsume rob her landlady, saw her wrongdoing and slashed her to death. On top of that, Shurei knows that the landlady’s Otama was the main culprit who killed Shikishima, and Shurei tells Otama that he will make her crime public, and if she doesn’t want to be public, she has to marry him instead. Otama reluctantly replies, but Shurei tells Otama to show her mind that she is serious. Otama has no choice but to kill her husband, Genshiro. However, everything is exposed and Shurei and Otama are about to be caught, but Shurei runs away. In the end Shurei commits seppuku. By the way, in Mokuami’s original, it is “Aoki Shurei”, but I noticed that it is “Akogi Shurei” in Kunichika’s painting. This “Akogi” is a word that indicates the meaning of “cruel and heartless”, and “Akogi Shurei” can be interpreted as “cruel and heartless Shurei”. The face of “Akogi Shurei” seems to be glaring from the bottom up, and the black eyes are glaring upwards to the point where they touch the upper eyelids. His mouth was tightly closed, and his cheeks seemed to be blushing with a thin layer of vermilion. This picture might look something like this: His face is filled with anger and suspicion at being told something unreasonable. Akogi Shurei is a quick-tempered samurai who wields a sword. The scene where frightened kagoya apologizes excessively then he goes into a frenzy. Or it may also be the scene where Akogi threatens Otama to kill Genshiro.

.

“Nakama Kanji” looks down, and only the eyes are looking at the opponent with upward glances. He looks like he’s grabbing a potentially interesting item with one hand, but the lantern is shining on him, his chin is tucked in, and his face is staring at something with disbelief and intimidation. The expression of “suspiciousness” that he is suspicious of something and doubts the opponent is drawn. The play was “Kichisama mairu yukarino otozure”(36), which was performed at Nakamura-za Theater in July 1869. Kojima Usui describes Nakama Kanji as appearing in the play(1). In the plot, his heir, Samonnosuke, is treated as a madman and imprisoned. Osugi, who secretly rescues it, drops the hairpin on the scene. The hairpin is picked up by Nakama Kanji, a villain middle guard. Here, the villain Nakama Kanji picks up the item as evidence, wonders what it is, and looks for the owner with his eyes.

“Yukanba Kichisan” has a downward-facing face, but is glaring at someone with upturned eyes. His mouth is slightly open, but his cheeks are grimacing. The area around his eyes is faintly painted in vermillion, giving him a spirited expression, which is truly an expression of anger. The story is from “Kichisama mairu yukarino otozure” performed at the Nakamura-za theater in July 1869. In the scene where the villains Benshu and Kichisan are talking, Benshu accidentally talks about the amount of money he got, and when Kichisan finds out about it, and almost threatens to take the money. The realism of the small villain was popular.

.

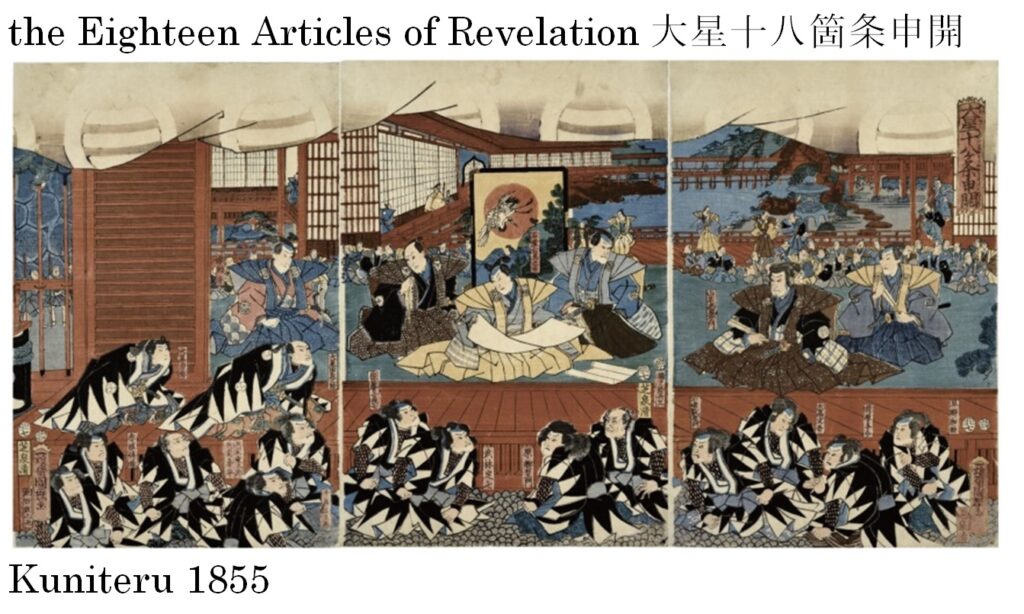

Ohoshi Yuranosuke is a character in the May 1869 performance “Naniobosi kanagakifude” at the Ichimuraza Theater. His face is upturned and his eyes are wide open. His eyes are staring at something and his mouth is closed in surprise. A scene from the famous Chushingura, as the title says “Juuhachikajou mousihiraki no zu”. Ohoshi reading a letter with important top secret information disguised as a love letter. At that moment, he realizes that Okaru, who was on the second floor, was looking at the letter. This picture shows his surprised expression, “Damn!”.

However, this painting is labeled “A Picture of the Eighteen Articles of Revelation.” In Kanadehon Chushingura (84), the story ends with the successful raid in the eleventh act, where Moronao’s head is taken. The Eighteen Articles of Revelation refers to the section (85) in which Oishi Kuranosuke was questioned by the shogunate after the raid, and this is a true story. The section shows Oishi calmly answering the questions, answering logically and based on the law, without any surprise or difficulty in answering the questions. According to Takahashi Wakako (86), the Eighteen Articles of Revelation can be seen in the Tsuji Banzuke and Ehon Banzuke from the Chushingura performance at the Nakamuraza Theater in September 1849, and in the Shinbutai Iroha Shojo performance at the Moritaza Theater in May 1856. Hasegawa Chubei’s ” The Eighteen Articles of Revelation of Oishi Yoshio” (87) contains the true story, starting from the Pine Corridor, through the raid, interrogation, and Oishi Yoshio’s suicide. From this, it is believed that the story of Kanadehon Chushingura was dramatized and the historical facts of the Eighteen Articles of Revelation were incorporated into the story and performed in kabuki. In 1855, Kuniteru painted ” the Eighteen Articles of Revelation” as the story of Kanadehon Chushingura from Act 11 onwards. Kunichika depicts Oishi looking up from below at Ishido Umanojo, who is being questioned, with tension and strong will, in this scene from the dramatized Kanadehon Chushingura. This may be the face of someone who is in a difficult situation, just like Benkei.